-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

Battling over the moral meaning of gender equality

July 26th, 2011 | LGBTQ, News, Views

Socio-political commentator Alex Au reviews a new book that analyses the wider implications of the 2009 AWARE saga.

By Alex Au

As the Singapore government gradually retreats from social engineering in the face of a better educated, more assertive generation, the vacuum so produced may not be filled by any consensus of what Singapore society should be like, but instead become a theatre of conflict, with different civil society groups pushing forward their ideas.

The March 2009 takeover of AWARE by a group led by Thio Su-Mien and Josie Lau, and its takeback two months later, may be a harbinger of things to come. Understanding why and how it happened will go a long way towards being able to see these conflicts with a wider perspective.

As it is, the AWARE conflict was seen by many as a clash between conservative Christianity and homosexuality. Indeed, the actors involved – a “new guard” motivated by Evangelical Christian antipathy to homosexuality on the one side, and an “old guard” with its secular ethos, allied with liberal and gay groups on the other – made such a reading almost inescapable.

That it came only 18 months after the loud public debate about Section 377A of the Penal Code – which criminalises homosexual acts between men – in which the conservative side was also strongly identified with Evangelical Christianity, only led people to see the AWARE saga in the same light.

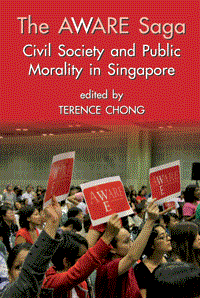

Yet, to read the event as merely a conflict between one religion and homosexuality would be to miss much of its significance. As the contributors to new book The AWARE Saga: Civil Society & Public Morality In Singapore (ed. Terence Chong, NUS Press, Singapore) take pains to explain, the fight has both deep roots and wider ramifications.

The AWARE conflict also raises many questions – about the influence of the US and a global Christian Right on religious thinking here, about the muscle power of hierarchical organisations versus that of flatter, more open structures – that need attention if one is to comprehend the more complex and variegated society that Singapore is becoming.

Chua Beng Huat’s and Terence Chong’s opening chapters situate the conflict in the context of Singapore’s social development and educational progress, arguing that as larger numbers of Singaporeans acquire higher education, a liberal-minded constituency inevitably grows. The government’s emphasis on economic progress, which entails an outward-looking, open economy, privileges this segment of the population.

As a result, cultural conservatives feel they are pushed to the margins. Moreover, whereas they could in the past rely on the government to protect moral conservatism, the government is increasingly giving this mere lip service while its actions contradict claims of conservatism – a trend that Chong describes as an abdication of its moral policing role. The decision to allow casinos comes to mind; the gradual retreat from penalising homosexuality too. Cultural conservatives will increasingly feel they need to take matters into their own hands to defend their interests. Seen in this light, the takeover of AWARE may not be the last of such moves.

Several chapters trace the events as they unfolded. Azhar Ghani and Gillian Koh detail the government’s hesitant and carefully calibrated response, in the process throwing light on their priorities and manner of working. Perhaps to the surprise of the coup-plotters, the government ended up showing itself to be more concerned about religious leaders wading into political and previously secular space, than about homosexuality. In the one instance when the government tapped on the brakes, it was the Thio group that lost out. A large number of its supporters were deterred from attending the Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM) that had been called to unseat the new guard.

Likewise, Loh Chee Kong’s analysis of newspaper coverage thorough the period – the Straits Times gave daily coverage to the contest – illuminates the thinking in the newsroom. Unfortunately, despite his allusions to the media straining at the leash of the government’s expressed desire not to dwell on sensitive issues, the opportunity to more exhaustively discuss how this tension might play out in the years ahead, come other civil society or public controversies, was not seized.

Curiously, the book does not include any chapter about the role played by the Internet in mobilising support for the old guard. Also lacking is a more in-depth portrayal of the new-guard actors. Throughout the book, they remain two-dimensional characters; one never quite gets to understand how they see a changing Singapore and why they chose to act in the way they did.

It is possible however that none of the authors could get access; if the record of the Thio group during the saga is any indication, they seem to be uncomfortable and reluctant to deal with the media and with intellectuals.

The EGM itself is brought alive, almost blow by blow, by Lai Ah Eng in her chapter. In doing so, she paints the incredible contrast in social cultures between the two camps. On the new guard side, there was orderliness and conformity to expected roles among its supporters in the audience, but also, after voting, a quick evaporation of interest.

Among its leaders, a shocking misjudgement of the mood, futile appeals to rank and quick calls on security guards to enforce their will wrecked their plans. Ultimately, they probably never understood that the difference between them and the old guard fighting to take back the organisation was not just a difference of opinion about homosexuality and morality, but a complete difference in culture. When rank and authority was discovered to mean little, the new guard was left with no other lever to engage and persuade.

Interestingly, the old guard itself misjudged its supporters. It had planned meticulously for who would speak and what to say at the EGM, but it didn’t take long for the rowdy passion and feckless spontaneity of their supporters to scramble their best-laid plans.

Through this recounting of the EGM, a significant bit of insight slips in. Here is a shift in the tenor of Singapore society that we would vastly underestimate if it is seen only within the confines of the AWARE conflict. It does not take much effort to see it again in the General Election of 2011; no doubt we will be witnessing more of such spontaneous, rebellious behaviour in other public issues to come.

Alex Tham throws more light on this phenomenon, from a different angle. In his chapter, he delineates the differences in organisation and social capital between the “new guard” and the “old”, arguing that while the “old guard” espoused an ethos of being open and inclusive, it in fact remained a small circle of women. This left it vulnerable to a takeover by a group modelled in contrasting ways.

Thio’s group was hierarchical, with enforceable trust, bringing to bear its greater social capital. The old guard, he writes, was saved not by its puny resources, but by the media defining this as a secularism versus religion debate, thus mobilising for the old guard the raw power of an incensed crowd.

However, Dominic Chua, James Koh and Jack Yong don’t even see it as a victory for liberals. Dissecting the language used, they show the links between Thio’s group and the Christian Right movement originating from the United States. Not only that, they show how the same language was adopted in other forums when discussing the AWARE conflict and homosexuality.

Since language shapes perception, in which direction has public opinion on homosexuality moved? As for the policy level, looking at the way the Ministry of Education scrapped the old guard’s Comprehensive Sexuality Programme right after the EGM, the conservatives might have won the bigger prize.

The chapters by Theresa W Devasahayam and Vivienne Wee try to look for meanings both in the conflict and after. Specifically, what did the new and old guards stand for? What models of feminism were in contest? Besides the issues of pluralism and secularism – which were an intrinsic part of the struggle, albeit played up by the media – there was a core difference in the understanding of gender equality.

Too often, the modern understanding of gender equality has one more value piggybacking on it: sexual autonomy. Proponents would argue that there can be no gender equality if sexual dis-autonomy, often framed by patriarchal rules, continues to operate.

The fight for AWARE reveals an intriguing idea brought by the Thio gang, albeit one that may be strongly shaped by their conservative Christian ethos: That there can be gender equality without rights to sexual autonomy, because, in conservative minds, nobody has rights to sexual autonomy, male or female, straight or gay.

Is this a viable proposition? Or is it so inherently problematic that such an idea can only be a smokescreen for the re-imposition of patriarchal systems?

The AWARE saga clearly provides much food for thought, and one good book, as this one is, may not be enough, only scratching the surface of the social trends and cultural questions the conflict represents.

The author is an activist and commentator on socio-political issues who blogs at Yawning Bread. The book The AWARE Saga: Civil Society & Public Morality In Singapore is available for $28 at the AWARE Centre (Dover Crescent Block 5 #01-22).

3 thoughts on “Battling over the moral meaning of gender equality”

Comments are closed.

A deeply insightful review by Alex Au. But that was to be expected from Alex. Who will give us “a more in-depth portrayal of the new-guard actors”?

I was there to support the old guard mainly because of their open liberal culture. I was also there partly because private conversations with evangelical Christians who feel no shame in demanding for a “Christian Singapore” and their perception of their god-given right to demand that non-Christians obey “Christian laws” irks me.

Nevertheless, I would like to point out that the use of the word “gang” to describe the Thio group conveys bias in the above generally neutral review. As in the extract below.

“The fight for AWARE reveals an intriguing idea brought by the Thio gang…”

Thank you for the review. I totally agree with the observation that “the government ended up showing itself to be more concerned about religious leaders wading into political and previously secular space, than about homosexuality”.