-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

Sex sells – but what messages about gender are you really consuming?

January 30th, 2012 | Employment and Labour Rights, Family and Divorce, Gender-based Violence, News, Views

Are today’s advertisements more sexualized? Or are they moving towards a more gender-neutral stance? Our January 19 Roundtable Discussion explored these issues by focusing on gender representations in the advertising industry.

By Veesha Chohan

Sarah Chalmers, an AWARE volunteer and a member of our Convention On The Elimination Of All Forms Of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) committee chaired the discussion. She opened by reviewing Article 5 of CEDAW, which links gender representations to advertising. Article 5 states that the social and cultural patterns of men and women should be modified with a view of achieving the elimination of prejudices based on stereotypical roles for men and women.

Three students from the National University of Singapore then shared a historical account of product advertising. Through their findings, we can see that there is a lack of advertisements that truly challenge pre-existing gender roles.

Sociology student Bryan Chia spoke about gender issues and sexuality in McDonald’s advertisements. His project was conducted as part of a Gender Studies module in 2011, and his qualitative study focused on gender stereotypes in McDonald’s advertisements. He found that almost all television commercials display some element of sexual stereotyping, due to the need to capture the audience’s attention through using relatable everyday norms, such as that of gender roles.

Singapore’s McDonald’s commercials seem to be shaded with moderate undertones of gender roles that are based on ‘family values’. It could be said that the purpose of these commercials is to “tug at the heartstrings of individuals” who could potentially identify with the protagonist in the advertisement. Most of these commercials highlight the difficulties of being a woman in today’s society.

A recent Singapore McDonald’s advertisement on Chinese New Year specifically mentioned: “My daughter has to juggle her job and look after the family.” In contrast, the men are shown to be sitting at a table during dinner, playing only inconsequential background roles. These commercials powerfully reflect social expectations with regards to the segregation of gender roles.

Sociology student Kellynn Wee looked at ice-cream advertising from both a historical and contemporary perspective. She drew our attention to the different ways in which advertisements have sexualised the female body, comparing the selling of silk stockings in the 1920s to the selling of ice-cream today. Just as silk stockings made legs a sexual asset, ice-cream commercials now use the female body as a sexual reference. The consumption of ice-cream is frequently represented in advertisements as an orgasmic act, for instance, and some ads play with sexual innuendo by not-so-subtly inviting comparisons between oral sex and the act of consuming ice-cream.

Kellynn believes that there is a need to de-naturalise the poses in these advertisements. Such sexualised ice-cream advertisements induce dual appetites implying the consumption of both the ice-cream and the woman.

Ice-cream advertisements have also shifted towards hyper-sexualising ethnic minorities, with cookies and cream ice-cream being marketed with African American women in the United States, for instance. The appearance of women in sexually inviting positions with their faces blocked out almost disembodies the woman. The woman’s body is not connected to her mind nor her emotions.

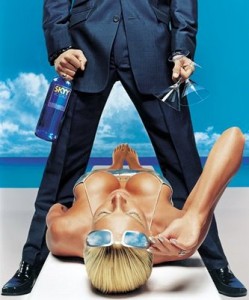

Social work major Nur Fadilah spoke about alcohol advertising, raising questions about why men seem to be the target audience for alcohol advertisements despite the increase in women’s socio-economic status.

If women appear in these ads, they appear as accessories to the man, who is normally depicted as being physically fit, masculine, and almost always white. According to Nur’s historical account of alcohol advertising, the 1950s was when hegemonic masculinity was linked to the consumption of alcohol.

This hegemonic masculinity was associated with middle-class men who played polo and golf. From the 1960s onwards, the good life for men was represented by women serving men alcoholic beverages while being placed in sexualised positions.

Because most alcohol advertisements are primarily targeted at younger males, women in these ads are generally portrayed as “man-eaters”, “rebels”, “party girls” or “prizes”. These representations of women are highly sexualised. Their body parts are sold to consumers along with the alcoholic beverage itself. Girls in these ads are permitted to be rebellious and daring, as long as they act in a cute and flirty manner. This is in sharp contrast to the representation of men, who are typically depicted as powerful, in control and strong.

Nur quoted prominent author and educator Jean Kilbourn, who believes that despite frequent criticisms that the media’s portrayal of sex is blatant and encourages promiscuity, sex is ultimately trivialised rather than promoted in the media. The problem is that the media tends to present sex as something that is “synthetic” and “cynical”.

Gender-based advertising that codes sex in this way almost inevitably reinforces negative connotations about women. These advertisements continue to marginalise the presence of women and their socio-economic position in society, despite the fact that we are living in a world where women are becoming increasingly independent and economically savvy.

Find out more about AWARE’s monthly Roundtable Discussion events here.