-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

Let’s Not Forget That Most Of Us Are Descendants Of Migrant Workers!

December 19th, 2012 | Employment and Labour Rights, Letters and op-eds, Migration and Trafficking, News, Views

Should we ignore the conditions of foreign domestic workers who work behind the closed doors of family homes, and have even fewer opportunities than male migrant workers to voice their concerns, much less organise an “illegal strike”?

By Vivienne Wee

18th December was proclaimed as International Migrants Day by the UN General Assembly in 2000, recognising the large and increasing number of migrants in the world. The International Labour Organisation estimates that there about 175 million migrants world-wide, with about half being workers.

Women comprise almost half of all migrants. It is widely acknowledged that migrant workers contribute to both the economies of their host countries and their countries of origin. However, many migrant workers are exploited and inadequately protected.

International Migrants Day is significant to Singaporeans: most of us are descendants of migrants, many of whom were labourers  working long hours for low pay. Some were rickshaw coolies who pulled the ‘jinriksha’ (rénlìchē 人力车 – i.e. human-powered carriages) – a common mode of public transport used from 1880 until 1947.

working long hours for low pay. Some were rickshaw coolies who pulled the ‘jinriksha’ (rénlìchē 人力车 – i.e. human-powered carriages) – a common mode of public transport used from 1880 until 1947.

In 1903 a Jinriksha Station was built at the junction of Neil Road and Tanjong Pagar Road for the government department set up to register and inspect the growing number of these vehicles. A plaque at this Station states: “For three cents, one could go half a mile (0.8 km), or for 20 cents, have the rickshaw at one’s disposal for an hour. Most rickshaw pullers were coolies, who laboured in the hope of saving enough money to return to China after their sojourn.”

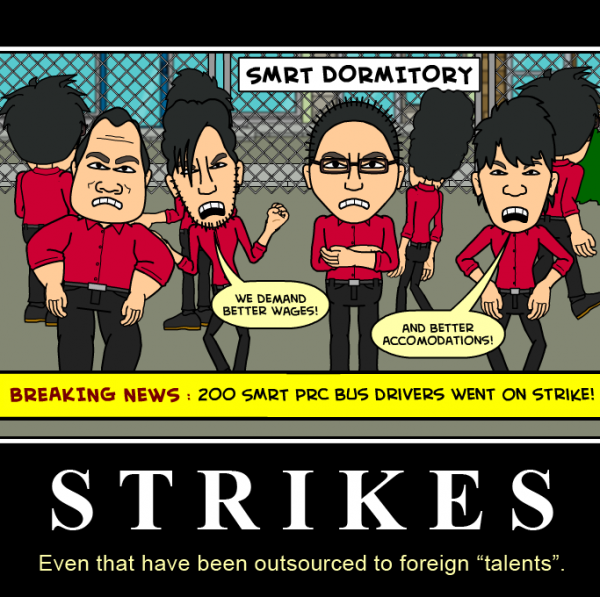

We no longer use human-powered carriages, but are migrant workers in modern Singapore any better off than those who laboured a century ago? What do we learn from the recent case of some 171 SMRT bus drivers from the People’s Republic of China, who did not report for work to “protest inequitable pay as well as poor work and living conditions” (Today 8 Dec 2012), including bedbug-infested dormitory rooms (Radio Netherlands Worldwide 18 Dec 2012)?

This protest has been defined as an “illegal strike”, with four of the drivers arrested, another sentenced to six weeks’ jail after he pleaded guilty, and 29 others deported.

The event has triggered intense debate about migrant workers’ wages, working conditions and living conditions, as well as employers’ accountability. Transport Minister Lui Tuck Yew has called for the employment terms and conditions of bus drivers to be improved, who are among the lowest-paid workers in Singapore.

Worldwide and in Singapore, women and children are particularly dependent on public transport for everyday needs. Would their safety not be compromised if migrant bus drivers who transport them are underpaid, overworked, poorly housed and disgruntled over such conditions of employment?

Worldwide and in Singapore, women and children are particularly dependent on public transport for everyday needs. Would their safety not be compromised if migrant bus drivers who transport them are underpaid, overworked, poorly housed and disgruntled over such conditions of employment?

In this year’s message on International Migrants Day, the UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, urged member states to remember that “whole sectors of the economy depend on migrant workers” and that “when migration policies are developed without attention to vulnerability, marginalization and discrimination, millions of migrants become cheap, disposable labour.”

The Ministry of Manpower estimates that our total foreign workforce (excluding foreign domestic workers) stands at 1,025,700 (as of June 2012). Just today, the eight companies providing most of the dormitories for foreign workers issued benchmarks for decent housing. Perhaps it is also time for the employers of foreign workers to set benchmarks for fair wages and decent conditions of employment.

There are about 200,000 female foreign domestic workers in Singapore who are not covered by the Employment Act. AWARE commends the Government for mandating one day off per week for foreign domestic workers, starting from 1 Jan 2013. However, no benchmark exists for their wages, working hours or housing. The oft cited reason is that it is difficult to check on the conditions of foreign domestic workers as live in their employers’ homes – but in fact, this points to the particular vulnerability experienced by these women.

Many governments, including Hong Kong and Saudi Arabia, do set minimum wages for foreign domestic workers. In Hong Kong, they are covered by the Employment Ordinance, with a standard employment contract stipulating rights and entitlements, including rest days, statutory holidays and conditions of housing.

The Singapore Government does prosecute employers and recruiters who commit criminal acts against foreign domestic workers. But how many more abuses go unreported, including abuses that fall short of being crimes? Should we ignore the conditions of foreign domestic workers who work behind the closed doors of family homes and have even fewer opportunities than male migrant workers to voice their concerns, much less organise an “illegal strike”?

While male migrant workers can, in principle, join labour unions, foreign domestic workers are not allowed to do so. What channels of redress are open to female migrant workers? They are potentially the most vulnerable migrant workers, who are nevertheless entrusted with the “essential service” of caring for us and our dependents.