-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

Guest blog: Queer liberation is a feminist issue: A Singapore primer

August 11th, 2014 | Family and Divorce, Gender-based Violence, LGBTQ, News, Views

By Leow Hui Min

In 2009, former law dean Thio Su-Mien proclaimed herself a “feminist mentor” and led a group from the Anglican Church of Our Saviour in taking over AWARE. She did so on the pretext of putting an end to an ominous and subversive “lesbian agenda.” She alleged that there was something suspicious about a feminist organisation that advocated for queer women.

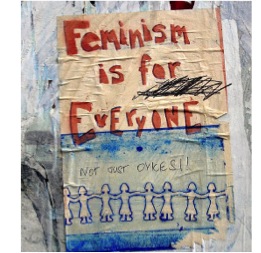

But as Flavia Dzodan has declaimed, “MY FEMINISM WILL BE INTERSECTIONAL OR IT WILL BE BULLSHIT!” [1]. What is intersectionality? Basically, it is the recognition that everyone in society holds multiple identities. Some identities are accorded a higher social status (privilege), and some of those identities are accorded a lower social status. For queer women, both queerness and womanhood are sources of marginalisation. An intersectional feminism must come to terms with these multiple axes of analysis.

In Singapore, colonial-era sodomy laws remain on the books, and the Media Development Authority actively censors queer-positive material as contrary to the public good. Its guidelines prohibit media that “glamourises” queer existence, but allows negative stereotypes and anti-queer propaganda to flourish in pulpits and newspapers alike. Marriage laws and immigration policies explicitly do not recognise same-gender civil unions lawfully contracted abroad, denying access to housing and other public services even to the couples with enough class privilege to obtain a partnership that’s legally binding somewhere in the world. To say nothing of the couples in a less privileged position.

Meanwhile, women participate in the labour force at a lower rate than men and for less pay. There remains marital immunity for rape, and the legal definition of rape remains pitifully archaic. MediShield does not cover birth control and the Ministry of Health mandates both unhelpful pre-abortion counselling and a two-day wait period. Sexism extends beyond these regressive policy measures and is cemented in societal attitudes such as casual rape threats in the armed forces.

More than that, though—at its heart, homophobia emerges out of sexism.

While much of Adrienne Rich’s opus “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” is questionable, she very insightfully points out that the “eight characteristics of male power in archaic and contemporary societies” enumerated by anthropologist Kathleen Gough also serve to enforce heterosexuality in women’s lives. “The chastity belt; child marriage; erasure of lesbian existence (except as exotic and perverse) in art, literature, film; idealization of heterosexual romance and marriage,” Rich writes—“these are some fairly obvious forms of compulsion, the first two exemplifying physical force, the second two control of consciousness.”

Singapore has found itself with an organised anti-queer movement straight-up transplanted from Evangelical Christian America. Their preferred euphemism for their bigotry is “pro-family.” In defence of their views on sexual morality, they trot out every naturalistic fallacy in the book. Penises belong in vaginas! Women have uteri, therefore conception is a moral imperative! Every child requires one [1] mother and one [1] father, genetically related, with only infertility justifying adoption (only by heterosexual, married couples)!

It is a worldview without any room for individual choice—a worldview in which “biology,” with all its socially and culturally inscribed meaning, is taken as destiny. And it is a worldview where a conviction in rigid difference between binary sexes leads to the exclusion of queer people. Firstly, sexism; thus, homophobia.

The “pro-family” argument is founded on the idea that men penetrate, women conceive; that men lead, women follow; that men discipline, women nurture. In theological terms, it’s called complementarianism. In secular terms, gender essentialism. Besides a failure to accept the reality of transgender existences and a failure to imagine a world outside the male/female binary, this way of thinking refuses to consider individuals as individuals—people with their own individual personalities, preferences, strengths, and weaknesses, and not some psychological checklist based on the “M” or “F” they were assigned at birth.

Some women are nurturing. Some men are nurturing. It’s always good to have a mix of personalities in any team effort (like child-rearing), but personality traits are not gender-specific, and parenting is not about mixing one part stern voice to one part sayang-sayang, adding water, and then expecting a happy family and healthy offspring.

Sexism gives rise to prescriptive ideas about women’s “essential nature.” The sexist conceptualisation of womanhood chronically demands heterosexuality and denies transgender identities. Because feminism is opposed to sexism in all its incarnations, straight feminists must address homophobia alongside queer women, and cis feminists must address transphobia alongside trans women.

When critics ask why AWARE supports the advancement of queer and trans rights, then, it is a failure of the imagination to appreciate the connections between different forms of marginalisation in society. That support emerges from the recognition that it is not only cisgender and heterosexual women affected by anti-woman sexism, from the understanding that many oppressions overlap, and from the principle of solidarity that should be at work in all progressive movements.

Leow Hui Min studies race and gender in media, and is a professional pen-wielder. It’s fun.

[1] Intersectionality, as articulated by Kimberlé Crenshaw in her 1988 paper “Mapping the Margins,” is a rejection of the call (in the U.S. American context) for Black women to put aside their racial identities in order to get a seat at the feminist table. That rejection is rooted in the fact that Black women cannot separate the racism they experience from their gendered existences, nor the sexism they face from their racialised lives. Moya Bailey coined the term misogynoir to describe that double-whammy.