-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

Recognise and support all mothers equally

May 7th, 2016 | Family and Divorce, Letters and op-eds, News, Poverty and Inequality

This article was first published on Mother’s Day at The Online Citizen.

Mother’s Day is especially significant this year. It comes shortly after news that equal maternity leave and a $3,000 Child Development Account grant will be available to all new mothers of citizen children, regardless of marital status.

Mother’s Day is especially significant this year. It comes shortly after news that equal maternity leave and a $3,000 Child Development Account grant will be available to all new mothers of citizen children, regardless of marital status.

When making this announcement, the Minister for Social and Family Development spoke of supporting unmarried mothers’ “efforts to care for their children” and his intention to “reduce the disadvantages that their children may face at birth”. Being unmarried does not reduce the value of a mother’s relationship with her child or the urgency of her family’s material needs.

Yet inequalities and deprivations remain for single mothers, both unmarried and divorced. If our society is serious about treating children equally and truly supporting mothers, we must go beyond alleviating the burdens of infant care to consider further structural barriers to their well-being.

First, we could do away with the legal concept of “illegitimacy”, which derives from English common law and which family law expert Professor Leong Wai Kum described as “ripe for abolition” in 2011. A child is only “legitimate” if her parents were validly married at birth. An “Illegitimate” child is, primarily, disadvantaged in inheritance law: they have no entitlement under the Inheritance (Family Provision) Act and are excluded from the definition of “child” under the Intestate Succession Act. Thus they have no claims if their father dies without a will, and succeed to their mother’s intestate estate only if she has no other “legitimate” children.

While statutory changes have reduced its scope over the years, “illegitimacy” is notable for directly targeting children, branding them as of lesser status because of their circumstances at birth. This is at odds with the government’s commitment to provide equal opportunities for all. It also produces curious outcomes, as in the case of one unmarried mother the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE) has worked with. This woman is attempting to legally adopt her own biological child to obtain more formal recognition and support – so that paperwork can bestow on the mother-child bond the “legitimacy” that apparently has not come from pregnancy, childbirth and years of care.

A second area due for reform is housing. Over the last year, AWARE has conducted in-depth interviews with over 50 single mothers (both unmarried and divorced) and over 20 children of such mothers. Again and again, the difficulty of finding and keeping housing has come up as a major obstacle to their improved well-being and socio-economic stability.

It is harder for unmarried mothers to access affordable housing because they can only buy Housing Board flats, as singles, when they turn 35. If they cannot afford a resale flat and need a subsidised HDB flat, they are only eligible for two-room flats in non-mature estates, which may not be suitable for their families. By contrast, their married peers, who may enjoy dual incomes, can buy subsidised HDB flats of larger sizes, in estates of their choice.

While other family members may allow these mothers and their children to share physical space, this can come with disdainful treatment and guilt-tripping, creating a hostile living environment. The financial pressures associated with housing also leave fewer resources for family life and the child’s well-being. It would be better to recognise an unmarried parent and their child as a “family nucleus” for the purpose of housing.

Although divorced mothers and their children can constitute such a “family nucleus”, they nevertheless face significant housing challenges. A number of our interviewees sold their matrimonial flats on divorce, enjoying little profit due to the mortgage and outstanding legal fees, and then faced a 30-month debarment period when they could not rent directly from HDB. Moreover, because many earned more than $1,500 (the rental income ceiling) but could not afford to buy a home, their options were extremely limited. Forced to rent on the open market, where the rentals per room can be several multiples more than when renting from HDB, they quickly depleted whatever resources they had. Navigating these challenges impoverished some who had initially been better-off.

A society which values caregivers should find this troubling. Motherhood has been a factor in these women’s impoverishment: many left employment during marriage to meet family care needs, reducing their savings and employability. Some earning just below the subsidy threshold were reluctant to earn more, as crossing the income ceiling could threaten their access to housing, and the possible gains in income were not large enough to compensate. Yet providing for their families on a household income of $1,500 has been a struggle.

The situation of these families would not be addressed by the forthcoming Fresh Start Housing scheme, which seeks to facilitate home ownership by second-timers with children. Instead, they need more straightforward access to rental housing once their marriage ends, such as a lifting of the 30-month debarment period and an increased income ceiling. As with unmarried mothers, sharing space with other relatives is often not an adequate solution.

Single mothers may appeal to parliamentarians for assistance, but not all individuals have the confidence and energy to navigate this process, which is time-consuming for both individuals and MPs. Moreover, not all appeals to MPs are effective, and the uncertainty of the outcome is highly stressful. In one case, a voluntary welfare organisation helping a single mother had to accompany her to plead loudly and dramatically at HDB’s premises before she could rent a flat. If the rules were changed to more unambiguously assure positive outcomes for more single-parent families, fewer cases would lead to such arbitrary processes.

As a mother myself, for Mother’s Day, I do not want the cakes or manicures peddled by advertisers this time every year. Instead, I want the hard work of motherhood to be given the value and dignity that it deserves, by a society that strives to meet the needs of all children and their mothers, regardless of marital status.

The author is the Programmes and Communications Senior Manager at AWARE.

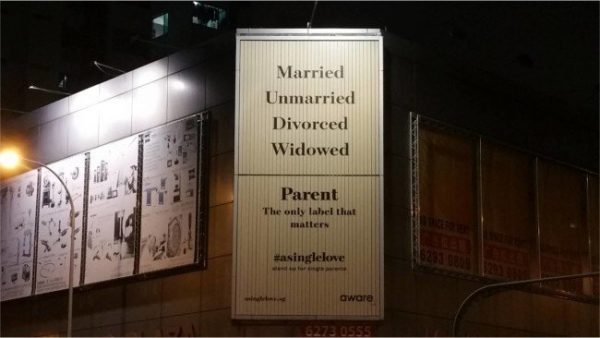

AWARE’s #asinglelove website- www.asinglelove.sg.