-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

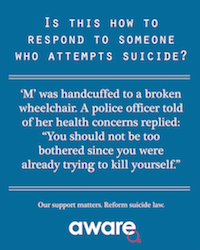

Our support matters. Reform suicide law.

March 2nd, 2017 | News, Suicide

Last September, AWARE called for the law criminalising suicide to be reformed – urging that it should no longer be an offence. We also made recommendations to improve first response so that persons attempting suicide – who are already in distress – are not further traumatised by experiences of arrest.

Last September, AWARE called for the law criminalising suicide to be reformed – urging that it should no longer be an offence. We also made recommendations to improve first response so that persons attempting suicide – who are already in distress – are not further traumatised by experiences of arrest.

This issue has gained attention in Parliament recently, with Senior Minister of State Mr Desmond Lee announcing in November last year that the Government is prepared to review suicide laws. Earlier this month, NMP Kok Heng Leun suggested that MSF consider having a specialist team to provide psychological support and mental health expertise and accompany the police when responding to cases of attempted suicide. MSF replied that the current approach of mobilising the Police “prioritises (the attempter’s) immediate safety” and “time taken to mobilise a larger team… may delay (their) response”. (See full text of question and answer).

Unfortunately, accounts from suicide survivors suggest that current processes are not adequately sensitised to their needs. One such survivor – M – contacted us and recounted how her arrest for suicide and subsequent referral to IHM left her worse off. Here is her story.

M’s story: Handcuffed to a broken wheelchair; a police officer told of her health concerns replied “You should not be too bothered since you were already trying to kill yourself.”

M experienced a series of traumatic events over four years, losing her mother, her marriage, custody of her child, her home and her job, and undergoing surgery that left her with a temporary loss of mobility. She felt like “a loser in life” and her depression eventually cumulated in a suicide attempt in October 2016.

She lit charcoal in the bathroom of a hotel room, planning to kill herself with carbon monoxide poisoning. However, police officers were at the door in five minutes, having been tipped off by someone else who knew about her attempt. A female police officer reassured M that they would only enter the room after she had gone to the toilet, so she unlatched the door. At least seven male officers dashed into the toilet within seconds, before M had barely pulled up her underwear. A frustrated and overwhelmed M then underwent two rounds of questioning.

The police handcuffed M to a wheelchair and brought her to a hospital for examination. The next morning, it was raining when M was discharged. She warned the officer that her leg had metal pins in it from an earlier surgical operation and that she had been advised by doctors to avoid contact with water. The officer commented that she should not be too bothered since she was already trying to kill herself. M was left speechless.

For one day, she was placed in lockup in a cold and dirty cell. Both her wrists were handcuffed to a broken wheelchair. Despite M’s request for a doctor due to her eczema, none arrived.

She was later warded in the High Dependency Unit at IMH for six days. There, she was traumatised by the screams and sight of other patients being tied down and sedated. M found it difficult to sleep and could only get 3-4 hours of sleep a night. One night, at around 1-2am when she could not fall asleep, she decided to read. A nurse on duty said that she could not read at that hour and that if she continued reading, she would be tied to her bed and sedated. Welcoming the thought of being sedated so she could fall asleep, M challenged her to do so and she ended up being tied down to her bed without sedation. M tried to bite herself free and another nurse had to intervene to stop her from doing so.

Overall, M felt that her she is worse off both mentally and emotionally after her stay at IMH and wished that the staff from both IMH and SPF had treated her with more empathy.