-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

Be child-centric all the way, including in housing

September 25th, 2017 | Children and Young People, Family and Divorce, News, Poverty and Inequality

An edited version of this piece was originally published as an op-ed in The Straits Times’ Opinion section on 23 September 2017. The print version as well as the initial online version contained a number of edits introduced by the newspaper without our consent. The Straits Times subsequently apologised and amended the online version; however, there remains one insertion by the newspaper which we did not agree with. The version on this page is the text that we submitted.

Children are a priority in Singapore. That was clear from the National Day Rally speech last month, which opened with a slew of pre-school education initiatives. Hearteningly, the Prime Minister referred repeatedly to social mobility, equal opportunities and a level playing field for all children – key drivers behind measures like KidStart.

But this child-centric ethos falters when it comes to housing for unmarried and divorced parents. Around 1,000 children are born to unmarried mothers yearly. From 2005 to 2014, more than 50,600 children saw their parents file for divorce.

MP Louis Ng recently presented a petition by seven such parents in Parliament, echoing a public petition organised by the Association of Women for Action and Research (Aware) with 8,000 signatures, overwhelmingly from Singapore citizens and permanent residents – including 2,200 members of single-parent families.

The petitioners in Parliament seek two key changes.

One is to allow unmarried parents equal access to Housing Board flats as married couples, instead of making them wait till they are aged 35 and limiting their options for subsidised flats to smaller, two-room units in non-mature estates.

Another is to allow divorced parents to access subsidised flats immediately, without any consent needed from their former spouse, even if care and control of the children is split (that is, each parent takes one or more children) or shared (that is, one or more children spend different parts of the week with each parent).

Currently, these rules present serious barriers to single parents accessing affordable housing on a timely basis.

The Government has argued that all benefits relating directly to children and their care are provided regardless of parents’ marital status. It draws a distinction between, on the one hand, support said to be more for parents, such as housing and child-dependent tax reliefs, and, on the other hand, child-specific measures such as maternity leave and Child Development Accounts.

Yet, reality is not so tidy.

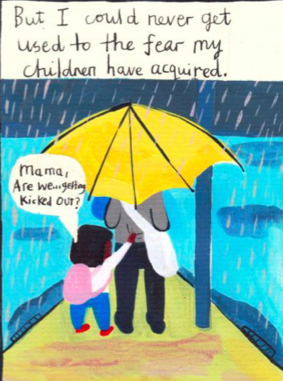

For example, can housing benefits really be said to be “for parents” more than for their children? The material conditions of children’s lives are inextricably bound up with the positions of their parents or caregivers. Children of divorced or unmarried parents end up having to move often if their parents’ living arrangements are insecure. They may cram in with relatives who, even if welcoming at first, can come to feel the strain from overcrowding themselves.

These vulnerable children’s family environments are marked by financial and emotional stress from their insecure housing. If their parents of limited incomes rent on the expensive open market, they may suffer from their parents’ depleting resources that could have been invested in their education.

Single parents pressing for change are driven not by individual monetary gain but by concern for their children.

Children have only one shot at growing up; no one wants them to spend precious formative years jammed three or four or more to a bed, uprooting every few years or months.

This intimate connection between parents’ circumstances and children’s welfare is embedded in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). The CRC is one of only three global human-rights treaties that Singapore has ratified, and it is invoked in the text of the parliamentary petition. The treaty, in discussing children’s rights to an adequate standard of living, including housing, phrases the state’s obligations in terms of measures to “assist parents to implement” this right.

The HDB’s debarment rules are one clear example where outcomes seem at odds with the emphasis on supporting children.

Presently, a divorced parent with children cannot get a subsidised flat within three years of divorce, unless she has care and control of all the children from her marriage; or can secure agreement from her former spouse to waive all rights to a subsidy of his own – no small sacrifice to ask for in the aftermath of a potentially acrimonious split.

If she has shared care and control (where the children move between parents during the week), she cannot get subsidised housing without consent from her former spouse even after three years.

The housing fate of divorced parents and their child can thus turn significantly on whether that child has siblings. A parent of only one child, with sole care and control of that child, has sole care and control of all children by definition and is exempt from the three-year waiting period to get subsidised housing.

But bigger families such as a divorcee with more children may find it harder to get subsidised housing because care and control may be shared or split.

This is an arbitrary, even perverse, outcome from the point of view of human need – a divorced parent with two or more children will need more space and more help – and especially given the Government’s exhortations to have more babies.

The Government may make the point that it needs to make sure public monies are sparingly spent – to prevent a divorce from increasing the number of households receiving subsidies from one to two.

But when care and control is split or shared, it is because a family court has determined that this is in the best interests of the children. It is a simple reality then that two households with children exist.

If we keep the needs of children at the centre of our thinking, we should provide the necessary support to help all of them get secure, affordable housing.

As split and shared care and control are comparatively rare, with judges generally keeping siblings together, the additional expenditure to support such households should be limited.

In any case, fears about the possible costs of child-centred thinking may be unfounded. Japan has found that reducing legal discrimination against unmarried mothers did not increase their numbers.

But we need look no further than our own past to see another precedent: unmarried mothers could access subsidised HDB flats until the mid-1990s. In 1994, then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong announced an intention to revoke this access in order to signal moral disapproval. Yet in the same speech he also acknowledged that “few children [were] born out of wedlock” under the status quo then prevailing.

It is ironic that so much is being done to boost pre-school education today to level the playing field for children from all backgrounds, when official policies tilt the playing field against a subset of children by making it difficult for their parents to get secure, affordable housing.

Children do not live only in the schoolroom. Our commitment to them must extend to all the spheres of their lives, including the homes which form the foundation of their family lives.