-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

A conversation on ageing and irrelevance

July 3rd, 2019 | News, Older People and Caregiving, Your Stories

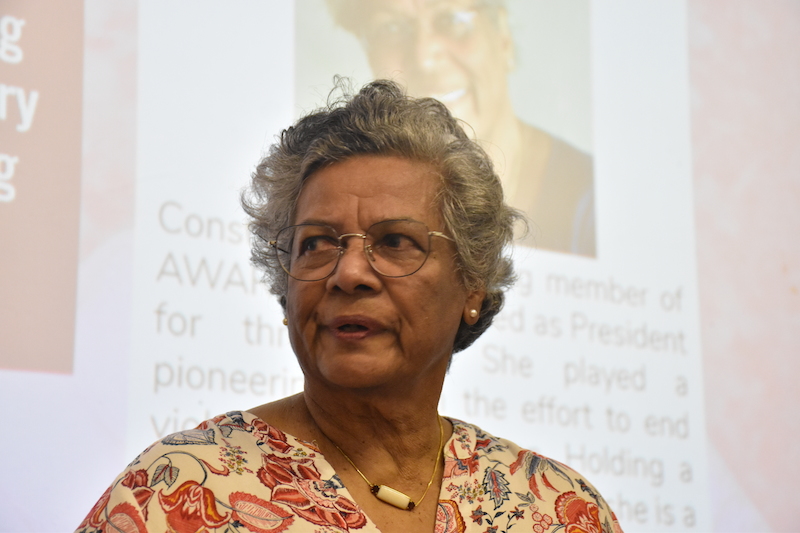

Written by Constance Singam. Photographs by Megan Tan.

This post was originally published on Constance Singam’s blog on July 2 2019.

“I am a foreigner in the land of old age and have tried to learn its language.”

“The trouble is old age is not interesting until one gets there. It’s a foreign country with an unknown language to the young and even to the middle age.”

– American poet and novelist May Sarton, who died in 1995 at the age of 83

I had not thought much about it ’til I arrived in this land of old age, and then only when I thought I had become irrelevant. And I have not stopped thinking about it since. I have written about it, talked about it and probably will go on talking about it.

I have written about loneliness and isolation. Which, I now think, comes out of being irrelevant and driven by a fear of illness.

So when did I start feeling old? I didn’t begin to feel old in my 60s. I didn’t begin to feel old in my 70s nor when I turned 80. But, last week, when I was talking about loneliness and old age, the penny dropped.

Loneliness and its resultant depression are the bedfellows of isolation and the feeling of irrelevance. That’s when I began to feel old. Two years ago, when I stepped off the fast lane of busy activities, I began to feel lonely and irrelevant. I have now worked myself out of that, thank goodness!

“Old age” becomes a condition in our view of ourselves when we feel irrelevant. That feeling of irrelevance and loneliness was dispelled when I realised that I have a community of friends. A community is a relationship of interdependence. It follows then that we are relevant to each other.

Busyness and activities are not what makes me feel needed and relevant. Meaningful relationships do. I didn’t come into this realisation that logically. Working through it helped and I did that when I talked at a gathering at AWARE.

AWARE had organised a session “Engaging Ageing: An open conversation for women”. The session, to my surprise, attracted about 40 people, many of them fairly young women. During the session we evolved into a community—a community that shared a concern. As we talked about our concern openly, we created a sense of togetherness.

A study in Finland found that a sense of community meant not only living with like-minded people but also communal activities, doing things together, learning from each other and having reciprocal support, all of which created a sense of togetherness, belonging and trust.

Church communities have historically succeeded in nurturing such communities. My mother, for instance, had for the longest time lived in Serangoon and had been involved in the Catholic Church in Serangoon Gardens. She was traumatised, lonely and isolated when she had to move away when she was 72 because the government acquired her land for redevelopment.

Earlier, when her children had grown up, with many leaving Singapore, she joined the community services at the Church, made friends and found that she could be useful, relevant and contribute to a community. She was happy again. But the move away at the age of 72 led to a long period of depression and feeling of isolation. I don’t think she fully recovered from that move.

A friend, also in her 70s, suffered a stroke the day she moved from her house to a new house and neighbourhood. She had lost a home she had lived in for almost 50 years, a familiar neighbourhood with friendly and supportive neighbours. She too never fully recovered.

For both my mother and my friend, their community—for my mother the Church, for my friend her neighbours—offered not just stability and the familiarity of a place and people but also an emotional connection. The more quality time spent in a community, the stronger the emotional connections. That emotional connection is important for any meaningful relationship and for individual wellbeing.

The other morning I was up early and I walked down to the local market. I seldom do this since my day usually begins only at 11am and the wet market closes at noon. But most of the hawker centre stalls remain open for the lunch-time crowd. The market is the centre of community life for the estate. It is a small estate and the hawker centre is a lively meeting place for the older residents.

I am a bit of an outlier partly because I am not Chinese and don’t speak the language and partly because I am not a regular. But having lived here for more than 20 years, I am a familiar face. I do get acknowledged with smiles, nods and occasional chats. And so it was that morning—the smiles, nods and chats, however insignificant, did lift my spirits.

But beyond the community life we find at the food centre, there is little in my HDB estate that creates opportunities for meaningful connections. We are a diverse group of people living in uninspiring blocks of buildings, and we are, for the most part, disconnected.

What can we do to create a greater sense of place in our HDB estates, a stronger sense of belonging and stability especially for older residents? The answer, I think, lies not so much in what the planners and policymakers should do but in what they should not do.

Yes, we need the policymakers to show more imagination and a greater sense of humanity as they plan, develop and manage our public housing estates. But perhaps what we most need is for the policymakers, the bureaucrats, to step back and create the conditions for residents to come up with their own ideas for community-building.

Ease up on the rules and regulations bit, and encourage residents to, for example, start cosy corners with potted plants in void decks where people can drop by for a cup of coffee and a chat. Let people be creative and experiment. Too much in Singapore is top-down, shaped by policymakers and implemented by bureaucrats. You don’t create communities with this approach.

DPM Heng Swee Keat says he and his team want to work with the people rather than for the people, and will partner Singaporeans in designing and implementing policies together. They can start by listening, really listening, and being open to fresh ideas, possibly crazy ideas. Encourage experimentation, try new things, be ready to make some mistakes and learn from them. In the process, we just might create communities.

For an ageing population the kind of neighbourhood communities we nurture would make a difference between ageing well in place and loneliness, isolation and depression.

Constance Singam is a six-time past president of AWARE.