-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

Survey finds that Foreign Domestic Workers face overwork, trouble remitting money and other obstacles during COVID-19

May 19th, 2020 | Employment and Labour Rights, Migration and Trafficking, News, Older People and Caregiving

Foreign domestic workers (FDWs) are facing unique challenges as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore.

AWARE and Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics (HOME) have been studying the role FDWs play in providing eldercare in Singapore since 2019, and wanted to see how the pandemic and subsequent circuit breaker measures have impacted them. We surveyed 25 FDWs in April 2020 while circuit breaker measures were in place, to see how their working and living conditions might have changed. All 25 respondents are currently looking after a person above the age of 67.

The survey revealed that FDWs are facing challenges on multiple fronts. These include their working and rest hours, their ability to financially support their families back home and the lack of a clear channel of communication between them and MOM for information about the latest COVID-19 advisories and work entitlements.

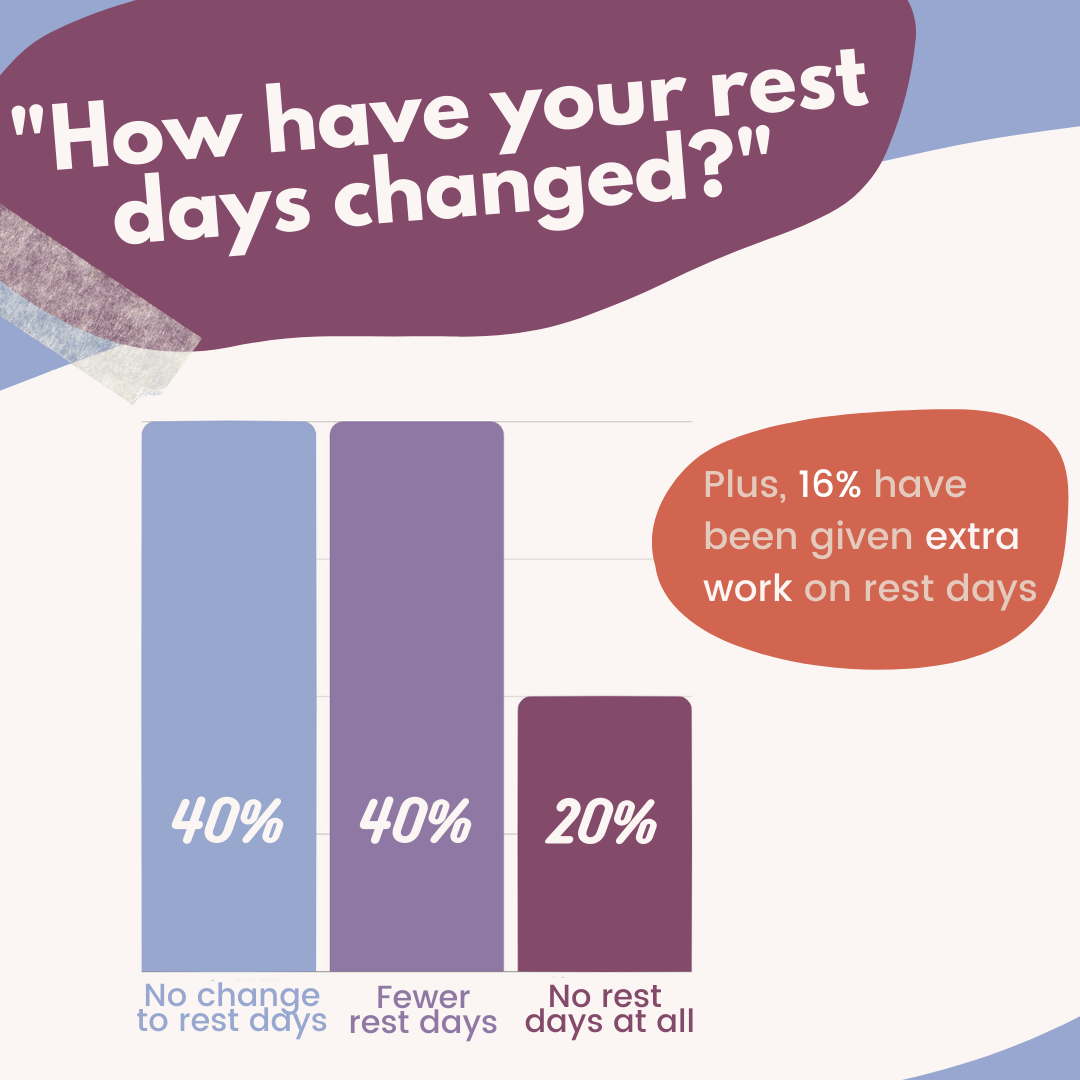

Forty percent of our respondents were taking fewer rest days during the circuit breaker, and 20% were working without a single rest day in the month. Compounding the risk of overwork, 16% of our respondents said they were given work on their rest days during the circuit breaker, when they had previously not been given any.

The International Domestic Workers Federation’s recent policy brief on the impact of COVID-19 on FDWs has highlighted overwork as a common problem across multiple countries. FDWs are particularly vulnerable to overwork, as boundaries are blurred when FDWs’ living environments are also their working environments. Overwork has a detrimental impact on both physical and mental health. Several respondents reported feeling very tired and uncomfortable. One respondent said, “Now I have to take longer to buy stuff because everyone [is] at home. Have to buy each person different food. The queue is always longer.” Another said, “Everyone is working at home now, so more work everyday.” Overwork could also affect FDWs’ abilities to provide the best care outcomes for the elderly they are looking after.

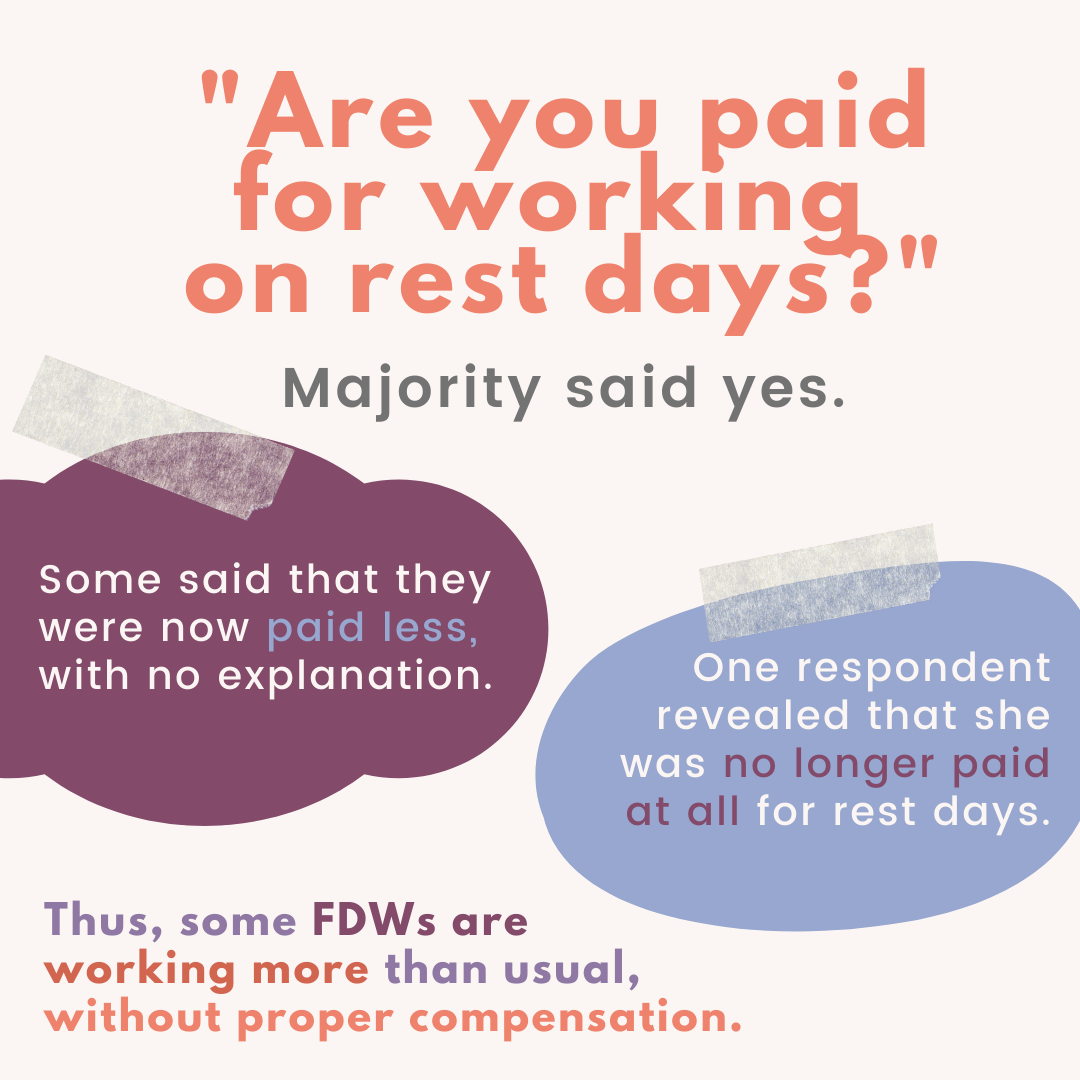

While most employers were paying them for working on their rest days, three respondents said that they were being paid less than their usual daily rate for working on rest days, with no explanation from employers. One respondent revealed that her employer no longer paid her at all for working on her rest days. Some workers are therefore working more than usual without commensurate remuneration.

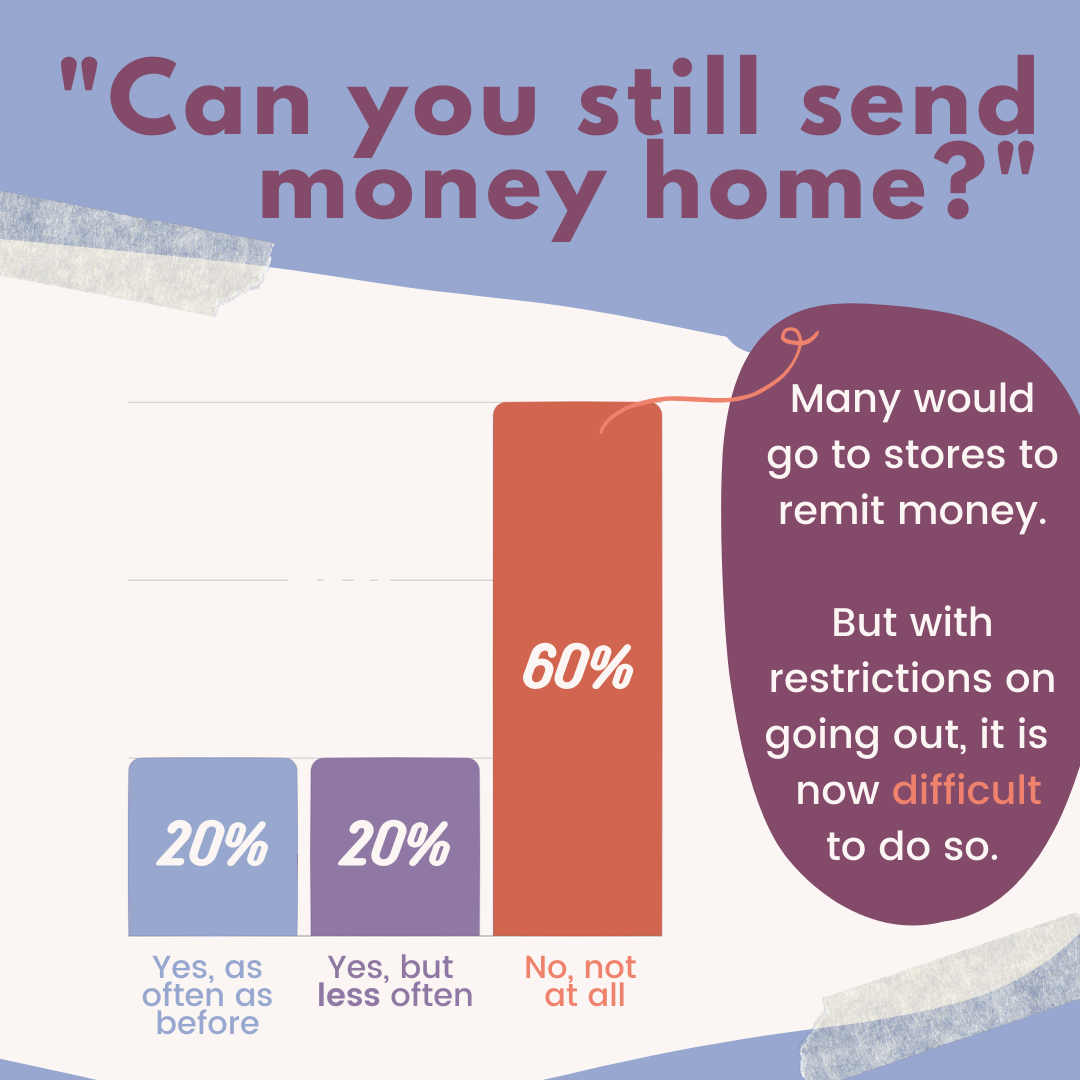

We learnt that 60% of our respondents are facing difficulties remitting money as frequently as they could previously as they are unable to leave their employers’ houses. This is especially worrying considering the majority of our respondents are married with children and need to support them. Twenty percent of our respondents said they are unable to remit money home at all, with one respondent saying that her children were having to pay for their own basic needs for the time being.

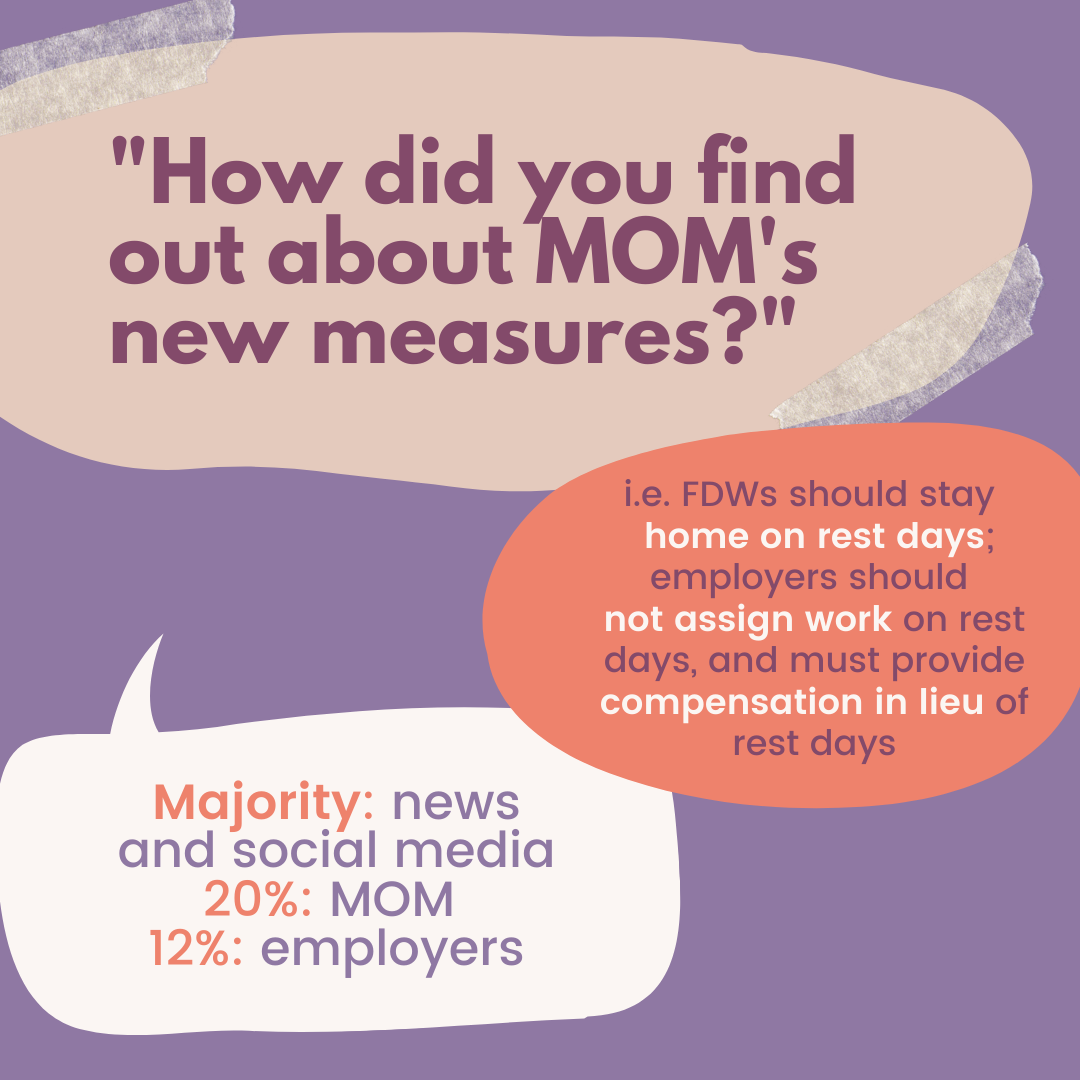

What exacerbates the above changes is the lack of clear communication to FDWs about measures affecting them. Only 20% of our respondents found out through MOM directly that they could no longer leave the house during their rest days. Even fewer, 12%, were informed of the change by their employers. The majority found out through various news and social media sources, which may not always be accurate. This could brew confusion about their entitlements during this period. Worryingly, 40% of our respondents did not know who to talk to if their employers did not follow MOM rules on working during their off days and necessary compensation.

When asked how FDWs thought MOM could help, they mentioned:

- holding employers accountable for fair compensation

- regulating the increase in their workload

- looking out for FDWs’ welfare when they left the house to run errands on their employers’ behalf

- providing increased financial support so they could look after their families back home.

One respondent highlighted the essential role FDWs play in supporting Singaporean families, saying, “[MOM] must care also [for] the FDW because they also part of a frontliner. Because they look after Singaporean family; they go outside to buy for the needs of the family.” Another asked for stricter enforcement by MOM, saying “They should at least make compulsory to the employer to pay FDWs if they don’t allowed them to go out and still work. Because some employers [are] really not following this rules.”

This survey reveals a need for authorities to ensure a direct channel of communicating matters that affect FDWs, during and beyond this disconcerting period. They also need to hold employers accountable for doing the same.

In addition, HOME has released a set of recommendations for how MOM can better support FDWs during this period. These include:

- issuing a clarification for employers that FDWs should be allowed to leave their house to complete essential errands, and for exercise, while observing safe distancing measures

- informing employers that FDWs should be paid their full salaries in a timely manner

- allowing a levy waiver for the next three months for all employers of FDWs

- facilitating the approval for work permit applications for all FDWs who are looking to transfer employers.

For more details, please refer to HOME’s full statement here.