-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

A Recap: Consent – do you get it? Youth perceptions on sexual consent

July 28th, 2020 | Gender-based Violence, News, Sexual and Reproductive Health

written by Kristen Teo, AWARE intern

When given hypothetical scenarios, young people in Singapore generally understand when consent is given or not. That was the conclusion of a new survey by AWARE and Ngee Ann Polytechnic of 539 youths, ranging in age from 17 to 25 years.

However when it came to their own real-life experiences, things were not so straightforward. Of the respondents who indicated prior engagement in sexual activity, only slightly more than half stated that they had discussed sexual consent with their most recent partner.

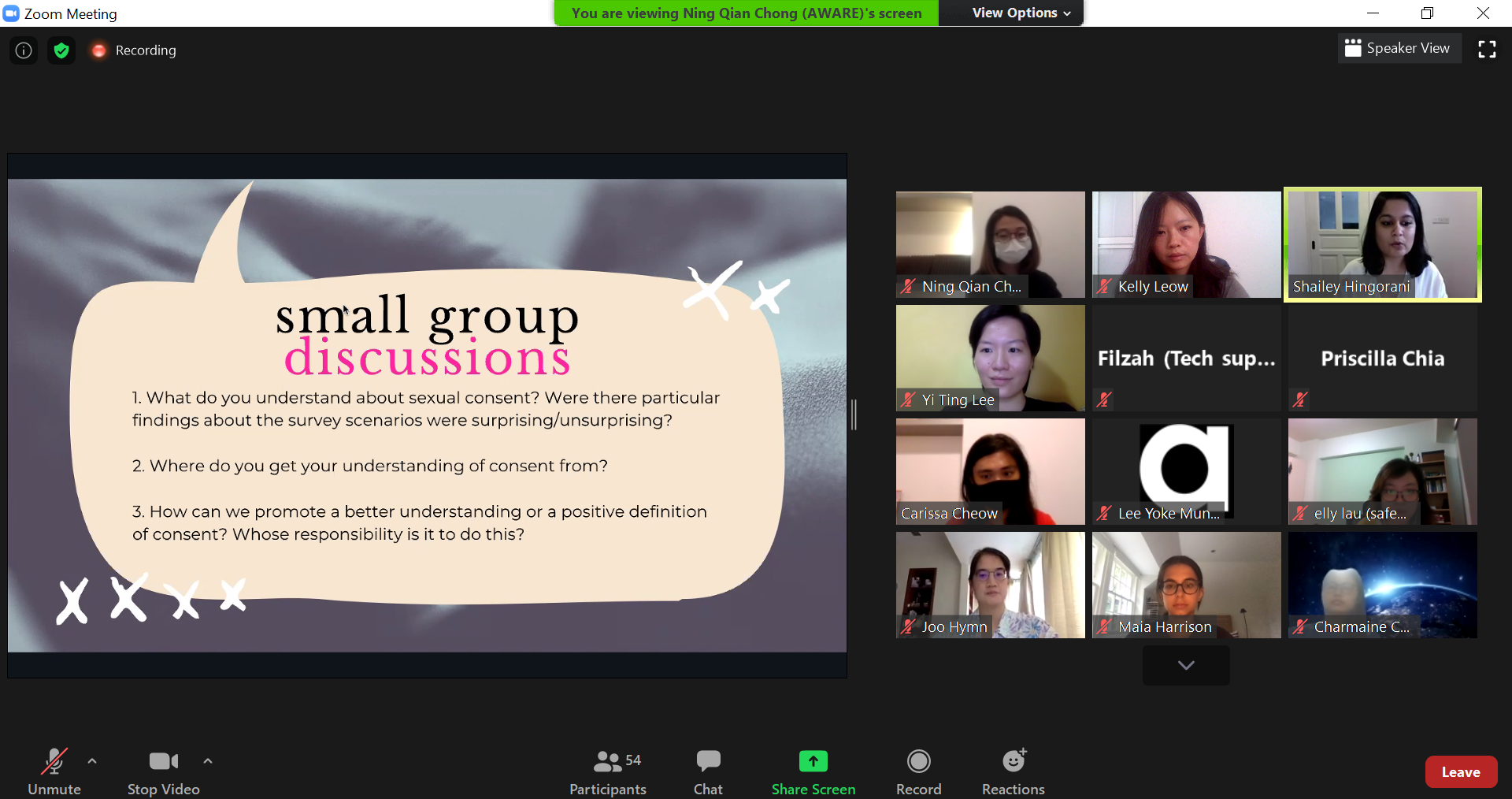

Why is there a disconnect between what youths know about consent in theory, and how they practice consent in their own experiences? What can we do to bridge this gap? These were some of the questions posed during the online event “Consent: Do you get it?”, hosted by AWARE on 25 July 2020. Around 50 attendees tuned in for a couple of hours to talk about how sexual consent can be more complex in reality than we think.

Leading this discussion were three panellists: public policy master’s student and co-president of SafeNUS Carissa Cheow, AWARE’s Birds & Bees workshop facilitator Lee Yi Ting and SACC volunteer lawyer Priscilla Chia. Moderated by AWARE’s Shailey Hingorani, the panel explored how youths today are learning about consent, the limits of sexuality education and some ways to normalise communicating and respecting consent/non-consent.

Survey findings

(Read the presentation, with more on the results, here.)

Understanding of consent

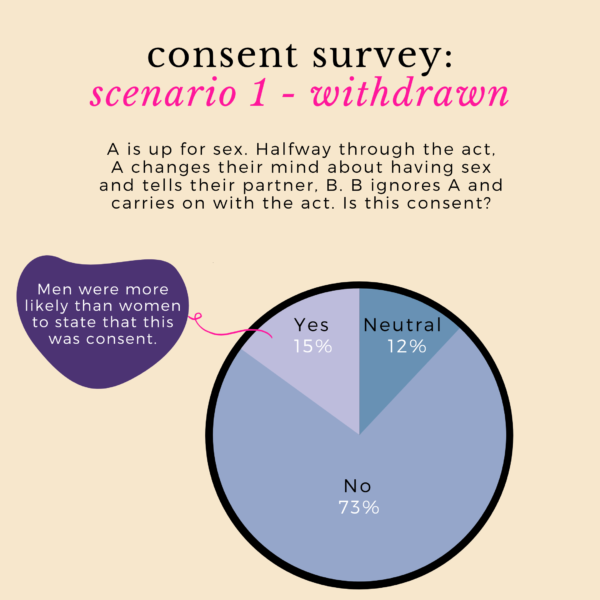

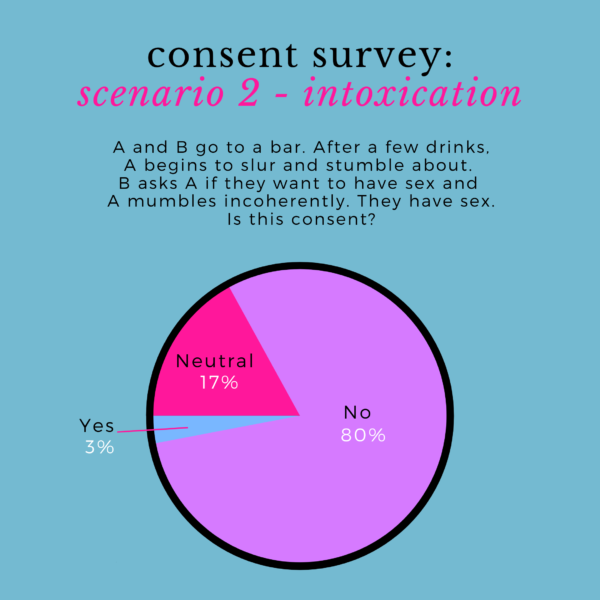

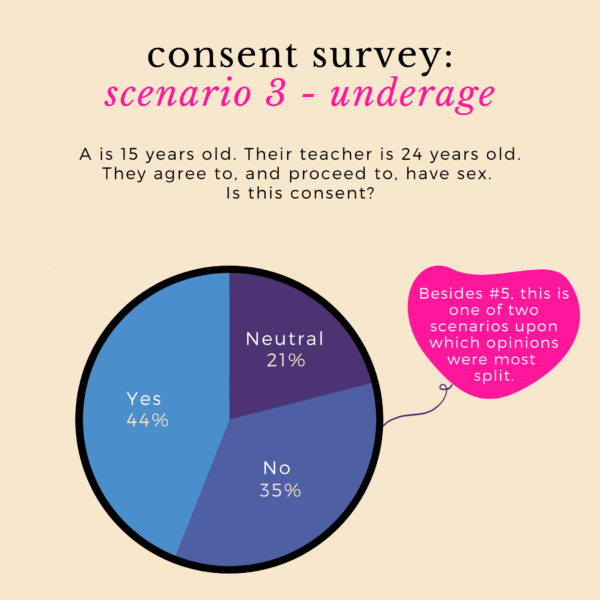

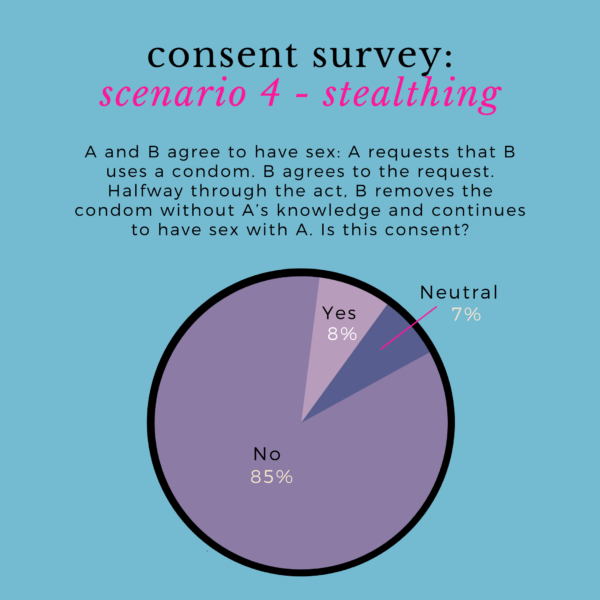

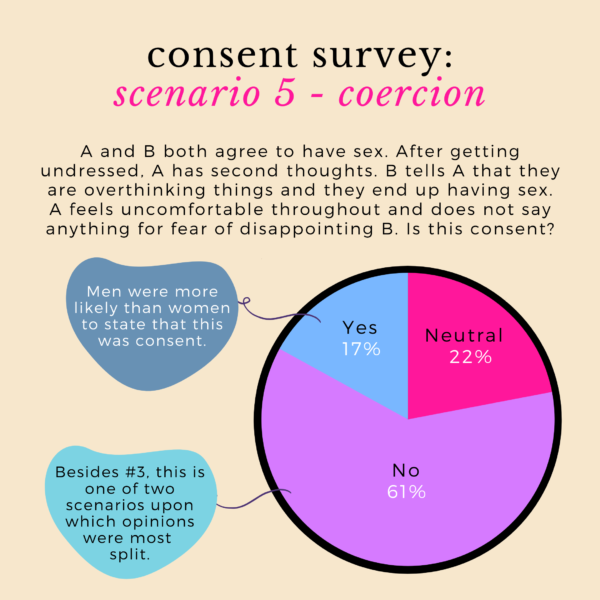

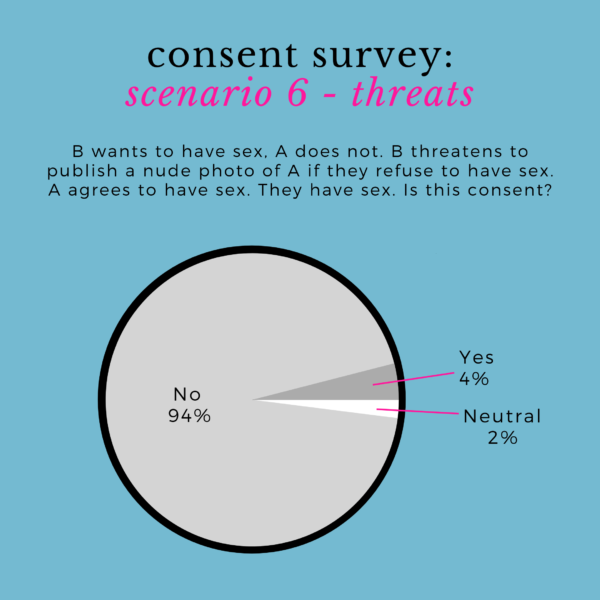

Majority of youths understood when consent had not been given over a range of scenarios, including when consent was withdrawn halfway through an act, or when consent was given under a state of intoxication or under threat. However, some were less sure when it came to situations involving a) underage sex and b) a reluctant partner being coerced or urged to say yes. Men were also more likely than women to identify some scenarios as consensual.

Attitudes towards consent and rape myths

Youths generally held progressive attitudes, though males were more likely than females to agree with problematic statements on consent and rape (for example, “most claims of rape are false”). Still, of concern was the finding that more than 1 in 10 young people believed that victims of sexual assault or rape had to “take some responsibility for what happened to them”.

Personal experiences with communicating consent

Of those who had engaged in some form of sexual activity (16%), majority (85%) said they asked for consent before initiating sexual encounters, but around one in three reported feeling awkward about asking for consent. Only slightly more than half had discussed sexual consent with their (most recent) partner before engaging in sexual activities.

Learning about consent

While almost all young people wanted consent to be taught in schools, less than half said they had actually been taught about it.

Sources of information about consent

Where are youths learning about consent from?

“There is still some level of division [among youth] today, and a lot of it still depends on where we get our information from, and who we discuss it with,” Carissa said.

Panellists posited that the Ministry of Education’s sexuality education programmes’ emphasis on abstinence and legal statutes may be difficult for some students to apply to their lives. As a result, many youth find themselves learning about consent from the internet and social media, or through peer groups. Conversations with friends are ultimately affecting how youth perceive the information they glean about sex from the media or elsewhere. While it is encouraging to see youths proactively talking about consent, panellists agreed that there are issues with learning about consent in such an unstructured manner.

Building on the importance of such conversations, Yi Ting gave examples about how MOE’s sexuality education curriculum may impede open discussion of consent. Speaking from her experience as a former Junior College educator, she noted, “When you’re focusing on abstaining from sex, you’re not really giving space to talking about consent and what it looks lke.”

In the survey, 97% of youths wanted consent to be taught in schools. Instead, Yi Ting recalled from her experience that MOE sexuality education spent more time on the negative consequences girls potentially face when they engage in sex—e.g. pregnancies and STDs—and less time on respectful interactions. Educators also bring in their gendered biases when teaching. One audience member shared that their sexuality education facilitator told girls that they had to be firm in saying “no”, as “boys can be pushy”—placing the onus on girls to avoid sexual violence, instead of on boys to not commit it.

Gaps between knowledge and application

The survey revealed that although many can recognise consent from a third-party perspective, they tend to second-guess themselves when it comes to their own experiences, wondering “Is this consent? Have I obtained consent?”

This is because there are personal stakes in real-life situations, panellists suggested. Many may feel hesitant to turn down a partner’s advances because they don’t want to hurt their partner or ruin the relationship.

In response, Yi Ting pointed out that there is all the more a need to cultivate a culture where people are attuned to various signs of consent and when it is being revoked—such as when a partner expresses that they are no longer feeling good mid-act.

Promoting a culture of consent

Panellists concurred that there needs to be a sustained engagement on multiple levels to construct a strong consent culture. Noting the importance of quality conversations at the peer level, Carissa asked, “How can we start this conversation with more people?”

With regards to education, elements of non-sexual consent can be taught at a young age. For example, parents can teach children that it is OK if they are not comfortable hugging a relative, as opposed to pressuring them to accept such contact. How we practise consent in non-sexual activity affects how we will practice it in sex. As Yi Ting put it, “Sex ed should not just be respected in a few hours of a school year.”

When it comes to social media platforms, we can practise cultivating consent by considering three stages at which consent may be violated: production, distribution and consumption of content. We need to consciously ask ourselves, “Am I implicated in violating someone’s consent in our digital interactions? Am I contributing to a culture of objectification, as opposed to a culture of respect?”

At the level of the law, there are channels available for individuals to share their concerns with policy-makers. Priscilla suggested that those who wish to see legal reform should write in to their Members of Parliament and make submissions via REACH.

She offered these parting words: “Don’t underestimate the power of yourself, of being part of that conversation. You can be the conduit of change.”