-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

AWARE’s Sexual Assault Care Centre saw 153 cases of technology-facilitated sexual violence in 2019, the most ever in one year

December 2nd, 2020 | Gender-based Violence, News, Press Release, TFSV, Workplace Harassment

This post was originally published as a press release on 2 December 2020.

* Correction notice, July 2023: When our analysis was performed, our system did not capture the full range of TFSV cases seen by SACC in 2019. We have since amended this post accordingly. We sincerely apologise for the error.

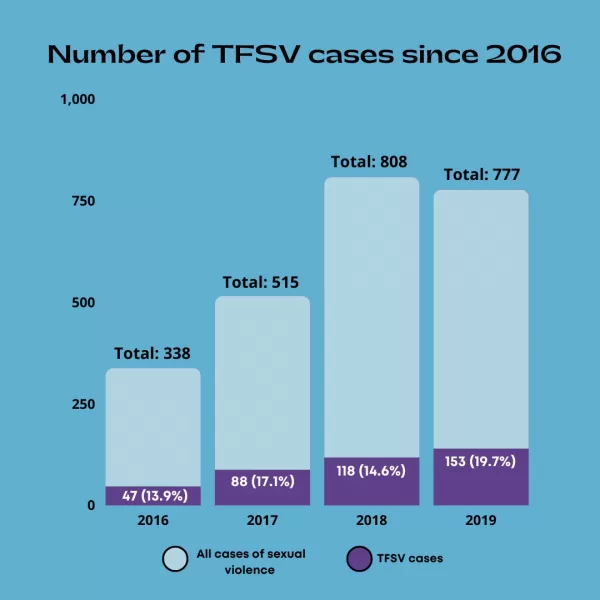

Gender-equality group AWARE’s Sexual Assault Care Centre (SACC) has seen the number of technology-facilitated sexual violence (TFSV) cases triple across four years. In 2019, SACC received 153 TFSV cases, out of a total of 777 cases (20%). In 2016, SACC received 47 TFSV cases (out of 338 total cases); in 2017, 88 (out of 515 total cases); and in 2018, 118 (out of 808 total cases).

AWARE defines technology-facilitated sexual violence as unwanted sexual behaviors carried out via digital technology, such as digital cameras, social media and messaging platforms, and dating and ride-hailing apps. These behaviors range from unwanted and explicit sexual messages and calls, and coercive sex-based communications, to image-based sexual abuse, which is the non-consensual creation, obtainment and/or distribution of sexual images or videos of another person. Image-based sexual abuse includes sexual voyeurism, the non-consensual distribution of sexual images (so-called “revenge porn”) and threats to do the above.

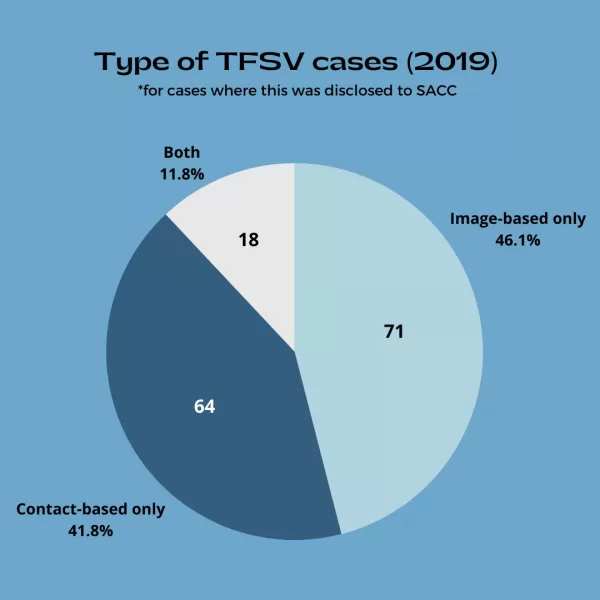

TFSV cases seen by SACC in 2019 included:

71 cases (46% of total) involving image-based sexual abuse

58 cases (38% of total) involving unwanted and explicit sexual messages and calls

18 cases (12% of total) involving multiple forms of abuse.

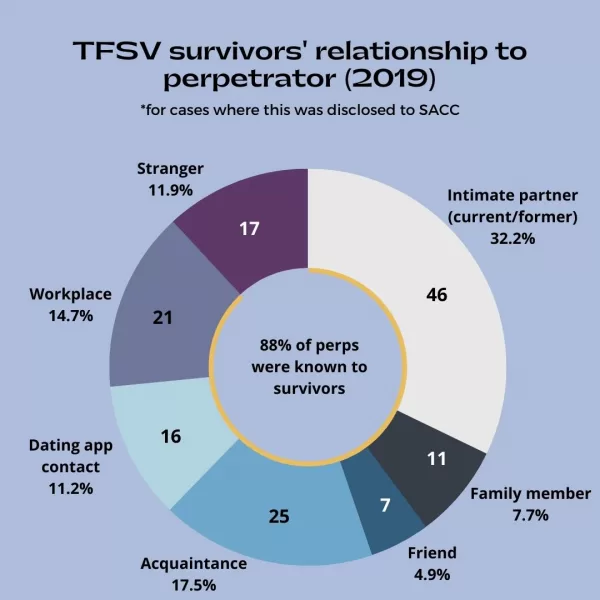

In most of the TFSV cases (8 in 10), the perpetrator was known to the survivor. Intimate partners (current and former), acquaintances and workplace colleagues formed the highest reported categories of perpetrators.*

While all TFSV cases involve an aspect of technology, the abuse sometimes occurs in offline spaces too, and can take the form of physical or verbal sexual harassment, rape, sexual assault (the three most common types of offline abuse), stalking, public humiliation or intimidation. In some cases, technology plays the role of connecting the perpetrator to the victim, i.e. via dating or ride-hailing apps. “Sextortion” is another emerging category, comprising 12% of cases, whereby the perpetrator obtains images of a victim without the latter’s consent, then blackmails the victim into having sex. The number of TFSV cases involving offline abuse remained high in 2019: Twenty-nine cases (19% of total) involved offline abuse facilitated by technology.

“The terms surrounding technology-facilitated sexual violence—from ‘upskirting’ to ‘SG Nasi Lemak’—have become depressingly common parlance in Singapore of late, given how often such cases are reported in the news,” said AWARE Head of Advocacy and Research Shailey Hingorani. “For many, the incidents no longer shock. When it comes image-based sexual abuse, we even know that men explicitly encourage each other to commit these acts over and over. So it is entirely unsurprising to see our case numbers going up. The trend is likely to continue.”

In SACC’s experience supporting TFSV survivors, staff have observed an emotional, mental and physical toll on clients, linked to their loss of dignity, privacy and sexual autonomy. This is exacerbated by the survivors’ limited ability to contain the spread of images and videos once they are uploaded and shared, and difficulty establishing contact with platforms to facilitate the take-down of these materials. As a result, perpetrators are seldom held accountable.

“For the sake of a perpetrator’s momentary pleasure or spite, a survivor may live with anxiety for the rest of her life, knowing that her images are being disseminated online to countless strangers,” added Ms Hingorani. “We hope that more education is provided to youth in Singapore to cultivate their empathy and respect, and counter the negative influence that they may receive on social media or other parts of the internet.”

AWARE has taken steps to expand its research and advocacy on technology-facilitated sexual violence. Earlier this year, the organisation held a contest to crowdsource initiatives against image-based sexual abuse in Singapore. One winning team is creating a centralised website with practical and up-to-date guidelines for image-based sexual abuse survivors to take action or seek support. The other winner is carrying out research into the various recourse options available to image-based sexual abuse survivors, evaluating their effectiveness, impact and limitations. Through these collaborations, AWARE aims to strengthen its recommendations regarding these types of sexual abuse.

Infographics

See previous information on TFSV at SACC here.

*This post was updated in 2021 to reflect more consistent categorisation of perpetrator type.

Annex

Technology-Facilitated Sexual Violence: Selected SACC Cases from 2019

Case A: The client received harassing and explicit messages and calls from her ex-partner shortly after she ended the relationship. The partner had non-consensually filmed the both of them having sex, as well as the client taking a shower and using the toilet. These videos were circulated online and to her family members. The harassment escalated to stalking and threats after the client blocked her ex-partner on social media. The client felt distressed and unable to focus on her work after the incidents took place.

Case B: The client was sexually harassed by her boss, who sent her lewd messages over WhatsApp, to which she did not respond. On several occasions, the boss made inappropriate comments about the client’s physical appearance. The case involved offline assault as well: On a business trip, the boss kissed the client without her consent.

Case C: The client was harassed by a ride-hailing driver on her way to work. The driver made explicit remarks, including how he liked to touch girls on the train. He also talked about women’s underwear as well as naked spa sessions. In shock, the client remained quiet throughout the ride and messaged a confidante. Eventually, with the support of her confidante, she reported it to the ride-hailing service company and is awaiting a response.

Case D: Sexual videos of the client were circulated on the internet. She had previously shared these videos with an intimate partner, whom she was no longer seeing. This former partner sent her friends screenshots of the videos with disturbing and explicit captions.

Case E: The client exchanged messages with a man on a dating app and the two decided to meet. Before they met, she communicated her desire not to have sex. The perpetrator agreed, assuring her he too was seeking a serious romantic relationship. However, when they met, he took her to a private space and raped her.