-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

A Recap: Violence in a Click, a panel discussion on technology-facilitated sexual violence

March 29th, 2021 | Gender-based Violence, News, TFSV

Written by Danesha Shah

On 6 March 2021, AWARE hosted a virtual panel, Violence in a Click—how do we close the tab on tech-facilitated sexual violence?, with the support of the High Commission of Canada.

The panel included the two teams working with AWARE under the “Taking Ctrl, Finding Alt” grant: Catherine Chang and Holly Apsley, who are currently developing a website for people experiencing online abuse in Singapore; and Lee Yi Ting, who is conducting research on image-based sexual abuse. They were joined by Tan Joo Hymn, facilitator of AWARE’s sexuality education programme for parents, Birds & Bees. The event was moderated by AWARE Projects Manager Filzah Sumartono, and was livestreamed on Twitter.

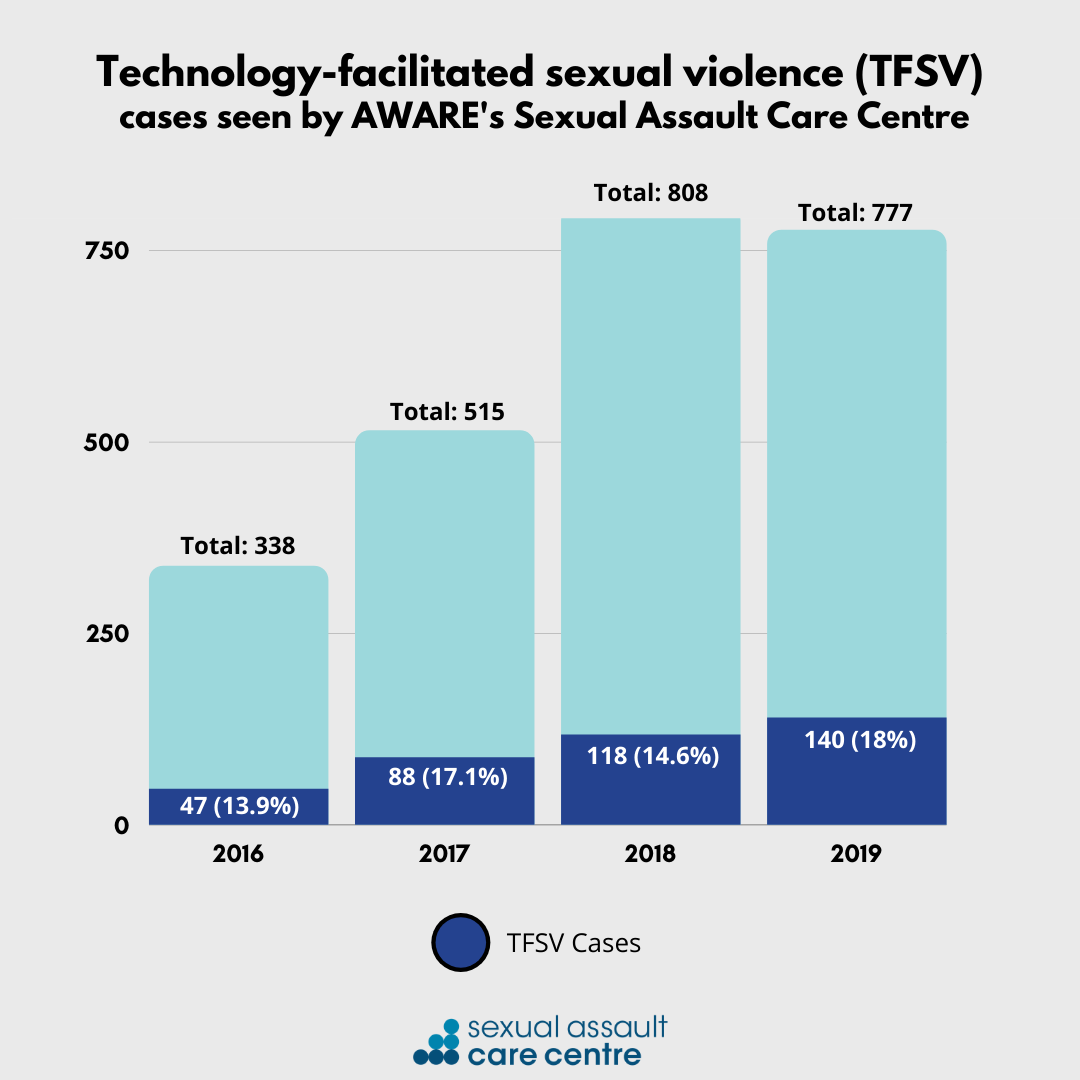

TFSV, or technology-facilitated sexual violence, is a type of sexual violence enabled by digital communications technology, such as social media and messaging platforms, digital cameras and dating and ride-hailing apps. These behaviours range from unwanted, explicit sexual messages and calls, to the creation, obtainment and distribution of sexual images without consent.

Based on interviews with survivors of TFSV, Holly explained that an important first step in their seeking help after an incident is recognising their experiences as sexual violence in the first place—as many think of violence as manifesting only as physical assault. She noted that this is why first responder training is important, as common victim-blaming reactions only serve to reinforce harmful myths about TFSV that prevent survivors from accessing support.

Similarly, Catherine said that many victims of online sexual grooming erroneously blame their own natural curiosity about sex, instead of perpetrators’ predatory behaviours, as the reason for their abuse.

When it comes to legal recourse after an experience of TFSV, Holly said that the prospect could be fairly complex. Although victims may be aware of some of the options that exist—such as pursuing a Protection Order under Singapore’s Protection from Harassment Act (POHA)—they anticipate that the process would be expensive and emotionally taxing.

Yi Ting added that seeking help from the authorities might also expose victims to retraumatisation and discomfort, for example when official personnel themselves examine the victims’ images.

Holly and Catherine explained that survivors can issue a Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) takedown order to websites hosted in the United States that contain their non-consensual images. However, it can be difficult for survivors to issue DMCA takedown orders, as images may be uploaded to and shared between an unlimited number of websites around the world every day. Although survivors can hire third-party takedown services, one of the team’s research respondents had said that these services charged her USD$199 for every website they contacted on her behalf. This process was obviously financially unsustainable (in addition to being retraumatising). Additionally, as the DMCA is a U.S. copyright law, it is only legally binding for websites hosted in the U.S., which limits the effectiveness of this option.

Other than financial constraints, some survivors may be unable to successfully remove or limit the spread of their images due to loopholes within platforms’ policies. For instance, one respondent had been unable to take down a link to an explicit picture of herself on Twitter, as the tweet itself did not contain the image. She found it difficult to dispute decisions made by the platform.

The panellists also discussed online pornography platforms as key players in the landscape of TFSV, both because they host many non-consensual videos, and because even consensually produced porn can impart harmful values in the absence of further conversation and education. Joo Hymn noted that because youth are being exposed to porn at increasingly younger ages, it’s imperative for parents and educators to teach that porn is produced for specific purposes, and often portrays unrealistic and non-consensual scenarios.

Holly added that these conversations must make clear the ethical differences between watching consensually produced pornography and viewing or sharing images produced or uploaded sans consent.

Joo Hymn stressed the importance of providing comprehensive sexuality education in schools as a means of tackling TFSV. She lamented that understanding of consent is so lacking, people often do not even think about asking for consent in everyday situations—e.g. when individuals take pictures of others and upload them onto social media without asking.

During the Q&A segment, the panellists addressed several questions that attendees posed via the chat.

One attendee asked about common myths surrounding TFSV. Yi Ting reiterated that many do not see it as a “legitimate” or “serious” form of sexual violence, while Holly highlighted that TFSV is often seen as a “women’s issue” although people of all genders experience it. Catherine pointed out that some oft-overlooked parts of survivors’ experiences include social isolation and practical changes to their daily life: Some survivors she had interviewed had changed their habits, for example paying for Grab rides instead of taking public transportation.

The panellists agreed with an attendee that a dedicated TFSV helpline would be helpful for survivors, pointing out that dealing with TFSV without external support is labour-intensive for survivors and emotionally taxing. Yi Ting added that an NGO that worked directly on TFSV, e.g. by organising support groups for survivors or facilitating digital security training, would be welcome.

Holly spoke about the importance of having workplaces that are understanding and supportive of employees who experience TFSV. For instance, workplaces can support an individual who is being targeted with harassment or stalking through a simple action like removing their email address from a company website, or allowing them to use a generic email ID that does not include their name.

Yi Ting stated that all companies, including social media companies, search engines and porn sites, need to be more responsible for ensuring that non-consensual images are not hosted.

As new cases of voyeurism and other forms of TFSV are increasingly reported in the media, Singaporeans are becoming more interested in curbing such acts of violence. Having conversations like this is critical in raising awareness and sustaining pressure on local stakeholders to urgently address TFSV.

View the slides from Violence in a Click here.