-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

AWARE saw 34% increase in cases of technology-facilitated sexual violence in 2020; announces launch of Solid Ground website

July 14th, 2021 | News, Press Release, TFSV

This post was originally published as a press release on 14 July 2021.

* Correction notice, July 2023: When our analysis was performed, our system did not capture the full range of TFSV cases seen by SACC in 2020. We have since amended this post accordingly. We sincerely apologise for the error.

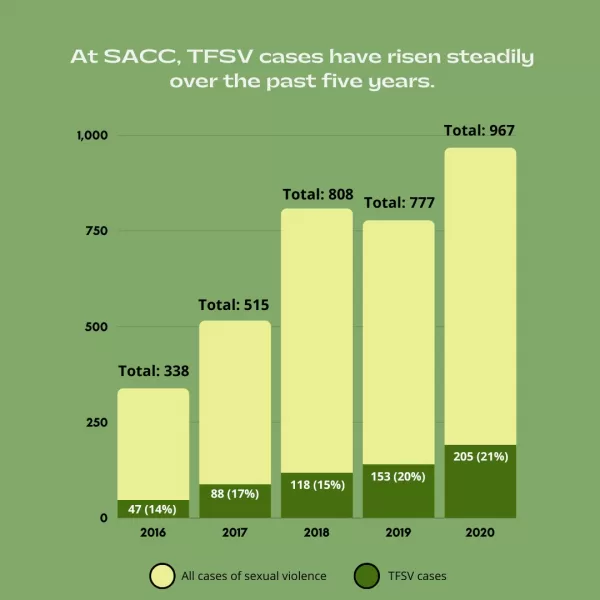

Gender-equality group AWARE’s Sexual Assault Care Centre (SACC) saw 205 cases of technology-facilitated sexual violence (TFSV) in 2020. This represents a 34% increase over 2019 cases (153), and the highest number yet since tracking began in 2016.

AWARE announced these latest statistics alongside the launch of a new website, Solid Ground, that provides practical information and guidance for TFSV victims in Singapore.

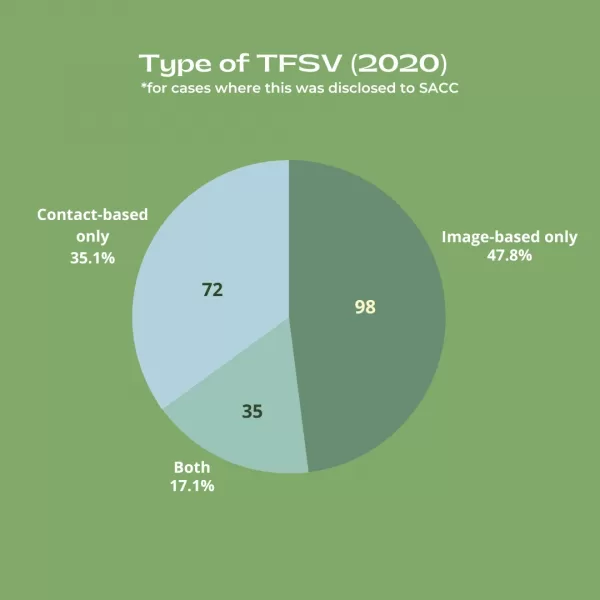

Technology-facilitated sexual violence is unwanted sexual behaviour carried out via digital technology, such as digital cameras, social media and messaging platforms, and dating and ride-hailing apps. These behaviours range from explicit sexual messages and calls, and coercive sex-based communications, to image-based sexual abuse, which is the non-consensual creation, obtainment and/or distribution of sexual images or videos of another person. Image-based sexual abuse includes sexual voyeurism, so-called “revenge porn” and threats to do the above. While all TFSV cases involve an aspect of technology, the abuse sometimes occurs in offline spaces too, and can take the form of physical or verbal sexual harassment, rape, sexual assault, stalking, public humiliation or intimidation.

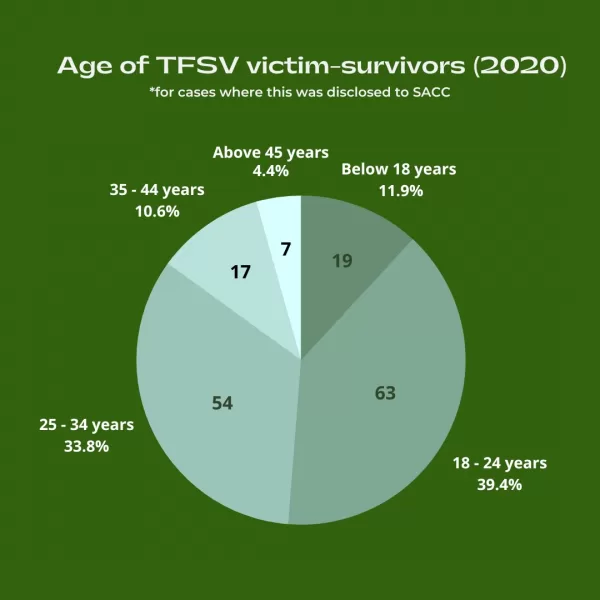

The victim-survivors seen by SACC in 2020 ranged in age, with the youngest being a tween and the oldest being 59. The highest number of cases fell into the 18-24 years age group in 2020 (63 cases, or 39% of cases where the age was disclosed): a significant jump from 2017-2019, when this category made up less than 30% of TFSV cases. The group with the next most cases in 2020 was 25-34 years (54 cases, or 34%).

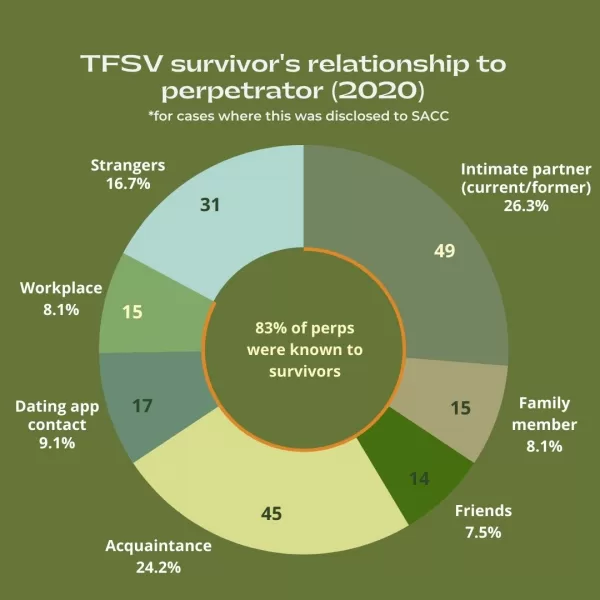

The perpetrator was known to the survivor in the majority of 2020 cases (where this was disclosed to SACC). Such perpetrators are typically far more common than strangers when it comes to sexual violence, perhaps all the more so during 2020 with COVID-19 circuit breaker measures reducing encounters with strangers. The highest reported category of perpetrators in 2020 was intimate partners, current or former (49 cases, or 26% of cases where a relationship was disclosed), followed by acquaintances* (45 cases, or 24%), which recorded a significant increase from 2019, then strangers (17 cases, or 8%). Other perpetrator types included family members, friends and persons from the workplace (though the last category saw a decrease in 2020, again possibly due to work-from-home measures).

“As our clients have attested time and again, the emotional, mental and physical impact of TFSV is on par with that of offline abuse,” said AWARE President Margaret Thomas. “It can include anxiety, depression, anger, guilt and suicidal thoughts. What’s more, there are often practical and financial effects: reputational damage, being forced to deactivate social media accounts, paying for a service to issue take-down requests to platforms, and so on.”

SACC clients experienced TFSV on a wide range of platforms, with some of the most common being messaging apps Telegram and WhatsApp, and social media platform Instagram. Ultimately, though, only 14 cases known to SACC sought assistance from the platforms, i.e. by making reports, seeking help with removal of non-consensual material and/or suspension of offending accounts. In most of these cases, however, survivors were not satisfied with the response from the platforms.

“We’ve seen an explosion in the means with which to perpetrate tech-facilitated sexual violence, but nowhere near a commensurate increase in the mechanisms to counteract it,” said Ms Thomas. “Users seem to have little confidence that platforms have their well-being at heart. We were cheered by the recent commitment made by Facebook, Google, TikTok and Twitter, in conjunction with the World Wide Web Foundation, to improve how they handle gender-based violence online. We hope to soon see this promise bearing fruit.”

In early 2020, AWARE held a contest called “Taking Ctrl, Finding Alt” to crowdsource initiatives against image-based sexual abuse in Singapore. One of the winning teams (Catherine Chang and Holly Apsley, both 24 and researchers at the Lee Kuan Yew Centre for Innovative Cities, Singapore University of Technology and Design) this month launched the website Solid Ground, which was developed in consultation with AWARE.

“Experiences of online harassment or abuse can be very isolating,” said Ms Chang. “Survivors need to privately and quickly find information to make sense of what happened and what they can do. When we couldn’t find a site containing this information in Singapore, we decided to create one.”

Solid Ground guides users through steps they can take if they experience any of nine common types of online harassment, such as being repeatedly contacted, being stalked online or having one’s personal information or images shared. Actions suggested include adjusting privacy settings, collecting evidence and applying for a protection order. The site also lists support resources in Singapore or online, and will be kept up to date to reflect changes to social media platforms’ policies over time.

“Many TFSV survivors are overwhelmed with gathering evidence, making reports, keeping themselves safe, managing their emotions and so on,” noted Ms Apsley. “We hope Solid Ground can be a place where survivors can catch their breath, find their footing and orientate themselves before taking their next steps.”

“Solid Ground is a port of call in the storm that is tech-facilitated sexual violence,” said Ms Thomas. “We’re confident that survivors will find it to be a comprehensive, thoughtful, action-oriented resource, one that meets a genuine need in Singapore.”

Solid Ground was funded by AWARE and the National Youth Council’s Young Changemakers Grant. At 8pm on Friday, 16 July 2021, Chang, Apsley and AWARE will hold a Twitter Spaces conversation to discuss Solid Ground and topics relating to TFSV.

Visit Solid Ground at solidground.sg. Join the Twitter Spaces event at @awarenews.

*“Acquaintance” is defined as a pre-existing relationship not covered by the other categories. Examples from 2020 include pastor, neighbour, classmate, doctor, coach and landlord.

Infographics

See previous information on TFSV at SACC here.

Annex

Technology-Facilitated Sexual Violence: Selected SACC Cases from 2020

Case A: The client discovered a public Telegram channel containing photos of herself and her own Telegram contact details. She had not consented to the photos being shared in public, nor had she known of the channel’s existence. She believes that the channel’s creator shared the link with a group with many members. As a result, she has been receiving unsolicited obscene messages and pictures of male genitals from strangers on Telegram. The client made a police report (outcome pending). She has also repeatedly asked Telegram to shut down the channel, but Telegram has been unresponsive. She feels very helpless.

Case B: The client found out that someone had been impersonating her on Facebook for years. The perpetrator actively posts details about the client’s life, pictures of her, as well as nude photos supposedly of her (though they are not of her). The perpetrator also uses this account to send messages to men, who then contact the client via her own real account.

Case C: After breaking up with her boyfriend, the client (and her friends) experienced sexual harassment from him over the course of multiple years. At one point, he created multiple social media accounts to stalk her. At another point, photos that she had posted on Facebook were uploaded to a Telegram group. There was even an instance of physical assault, which she reported to the police. The client decided to go on unpaid leave in order to stay home and away from the perpetrator.

Case D: The client got to know a man through an online dating app. However, after some investigation, she discovered that he had been using a fake name and lying to her about many aspects of his identity and life, including the fact that he had a girlfriend. He showed her nude photographs of other women, which led her to believe he was also sharing her own nude photographs with other individuals. She felt disappointed that their relationship had begun on false pretenses.