-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

A Recap: Beyond the Bare Necessities – Gender & Minimum Income Standard in Singapore

January 28th, 2022 | Family and Divorce, News, Poverty and Inequality

by Khaing Su Wai

What is the true cost of a life well lived in Singapore?

More than 90 attendees tuned in on Thursday, 13 January 2022 to find out the answer at an online panel discussion about the recently published Minimum Income Standard (MIS) study and its intersection with gender.

Titled Beyond the Bare Necessities: Gender & Minimum Income Standard in Singapore, the panel featured Teo You Yenn, Associate Professor, Provost’s Chair and Head of Sociology at the Nanyang Technological University; Ng Kok Hoe, Senior Research Fellow and Head of the Case Study Unit at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy researcher; and AWARE’s Executive Director Corinna Lim. Taking up the role of the moderator was Ng Bee Leng, a long-time social worker.

This event followed the late-2021 release of a study, supported by AWARE and conducted by a team including Kok Hoe and You Yenn, that shed light on the amount needed for a household of parents and children to meet their basic needs in Singapore. The study employed the MIS approach: an internationally recognised research method that has been used in the United Kingdom since 2008. This is the second MIS study in Singapore; the first study in 2019, by the same team, focused on the lived realities of older Singaporeans aged 65 and above.

1. The cost of living well

The MIS team, represented by You Yenn and Kok Hoe, determined that a couple with two children (aged 7-12 and 13-18) needs $6,426 a month, while a single parent with one child (aged 2-6) needs $3,218 a month.

With some eye-opening graphs and tables, Kok Hoe brought the attendees through the process of calculating this: MIS participants were first asked to list the services and items required to live well in Singapore. Experts were consulted for the price range as well. After the prices were tabulated and compiled, participants had to agree to all the items listed before the income range was determined.

From the budget, the components that made up the largest bulk of people’s expenses were food, housing, education and childcare costs. Kok Hoe said that when these income benchmarks were compared with the median average household work income, the MIS team found that 30% of households fell below the median income. Of these households, many might belong to workers in lowest paid occupations or casual employment, and/or those with lower education levels.

How does gender factor into the equation, then?

2. Intersection of gender and income

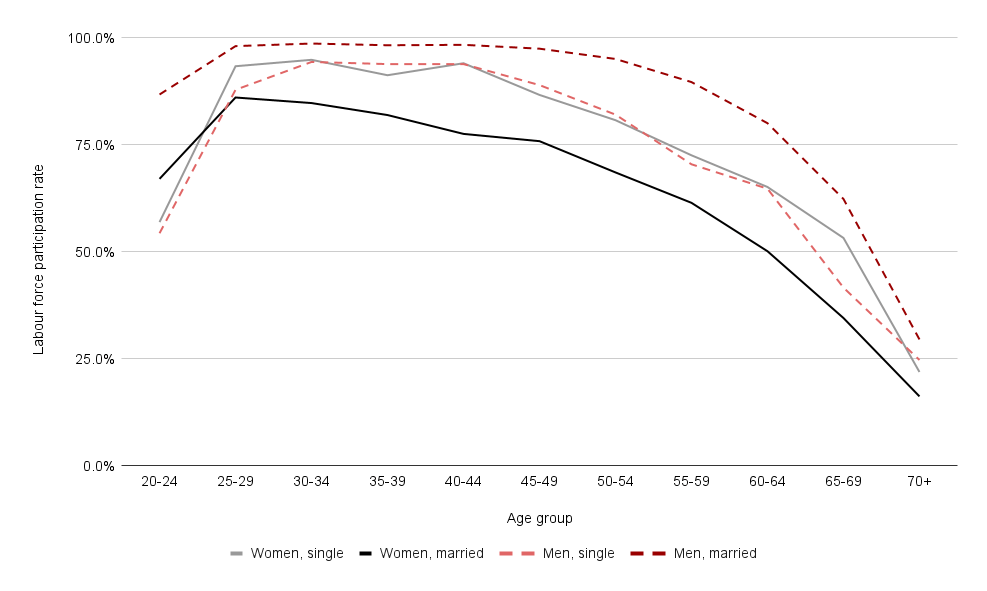

Kok Hoe emphasised the importance of thinking about gender when studying income, especially in Singapore, where the gender gap has remained consistent at 16% over the past decade. When it comes to both labour force participation rate (LFPR) and income, women receive the shorter end of the stick: Kok Hoe shared a graph showing the sharp drop in women’s LFPR in age cohorts from mid-20s onwards, while men only noticeably started leaving the workforce in their 50s. Married women in particular had much lower participation rates when compared to single women, which visibly affected their income levels.

You Yenn went on to explain that the discrepancies we see in the data aggregated by gender and marital status boils down to distribution of household roles. Research participants “tend to assume that the male partner is the one who is working while the female partner is tending the household”. The research team observed that these gendered assumptions about employment crossed over into other aspects of life, such as household management and eating patterns — e.g. participants presumed that a wife understood the needs of a household better than a husband. When it came down to education, both sets of parents were able to eloquently articulate concerns about their children, but there was a strong indication that mothers were the ones who primarily supervised children’s progress.

Panellists explained at length why children’s education needs in particular affected women more than men. Mothers were more likely to take time off their leisure hours to care for children, whether it be for homework supervision, commuting or school meetings. You Yenn spoke of the social expectation that mothers should be the ones to cut back on hours or opt for job flexibility for children’s needs, and, conversely, the social stigma that men faced when they took up the role of the primary caregiver.

“It’s important to recognise that what appear to be personal choices are social phenomena,” You Yenn emphasised, stating that individual decisions are not made in a social vacuum. This was a pattern observed by the researchers over and over during the MIS research process: For example, fathers were more likely to consider tuition an unnecessary expense, which often left mothers to pay for tuition on their own as a last resort.

This inequality is amplified for single parents, who tend to be women. You Yenn relayed anecdotes from her research experience that indicated single mothers’ tendency to regard childcare as a precondition to participate in social activities. They were also often managing to live with less than they needed.

She concluded that what people spent on is not not always reflective of what they need — in fact, it could mean they are forgoing certain needs.

3. The road ahead

The panel agreed that gender inequality today could be alleviated by ensuring fairer allocation of government resources. On the topic of future policies, You Yenn hoped to see more attention directed to bettering care infrastructure and education.

Corinna was in tandem with You Yenn, agreeing that the amount of private investment that parents currently channelled into education was not sustainable. She referred to the shortcomings in the education infrastructure as a warning sign. She also highlighted eldercare infrastructure as another area of immediate concern — one that could head down the same path as our education system, with its demands for private resources and individual effort.

For Kok Hoe, universal wage topped his policy wish list: “Universal wages would help not just women but all workers. There is a mental block against talking about minimum wage, but as long as we have wage standards, it’s a good ladder.” He spoke of his dream to see all discriminatory policies eradicated, and suggested implementing a litmus test, whereby policymakers carefully consider whether a new policy would discriminate against any vulnerable groups before implementing it.

“Gender equality is a deep structural problem.” said Corinna, “Part of the solution is awareness — sharing the issue with others and coming together with people to understand it.”

Panellists expressed their delight in the event’s high attendance and engaged audience, who actively posed queries throughout the panel. Bee Leng wrapped up the robust session by encouraging attendees to examine gender inequality in their own spheres, and to support organisations who are actively working towards evening the odds for marginalised communities.

“The speakers were brilliant at explaining their findings and [keeping] the audience engaged,” noted one attendee in the feedback form. Others also said that “the detailed perspective on the subject matter was enlightening” and they appreciated the “macro perspective bringing in international insights and tying it to the local context”.