-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

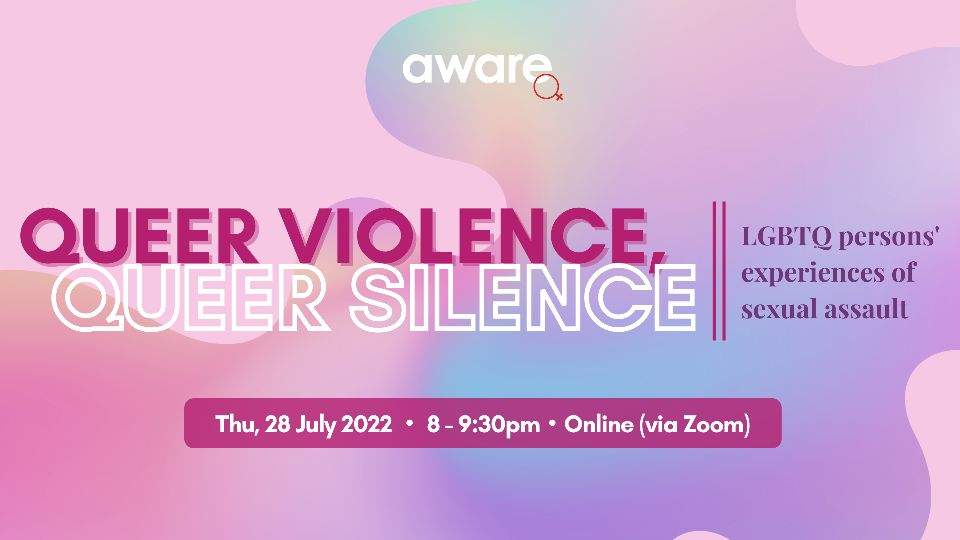

A Recap: Queer Violence, Queer Silence: LGBTQ persons’ experiences of sexual assault

August 20th, 2022 | Gender-based Violence, LGBTQ, News

Written by Varsha Sivaram

Trigger warning: This recap includes discussion of sexual assault and discrimination against LGBTQ people.

On 28 July 2022, around 50 people attended the virtual discussion “Queer Violence, Queer Silence: LGBTQ persons’ experience of sexual assault”.

Moderated by Lee Yi Ting—a former sexuality education facilitator at Ministry of Education (MOE) schools—the panel featured AWARE Executive Director Corinna Lim, Sayoni co-founder Jean Chong, and educator, poet and playwright Jaryl George Solomon.

Amidst the rise of the MeToo movement, the absence of LGBTQ people from conversations around sexual violence has been notable. While research has shown that LGBTQ people are particularly vulnerable to violence, their experiences are still not a part of mainstream discourse.

The panel discussed the many issues that LGBTQ victim-survivors face, from violence-related stigma both within and outside of the community, to a lack of accessible support.

A victim-survivor’s perspective

Sexual assault in LGBTQ communities, Jaryl said, is “shrouded in shame” on multiple fronts, leading to a lack of conversation and an inability for others to adequately affirm, support and comfort victim-survivors.

As a queer survivor of sexual assault, Jaryl said that he had struggled in the past with finding the vocabulary to talk about his experience. Without specific education on the issue, he initially did not understand that his experience constituted sexual assault in the first place. He initially discounted the authenticity of what he had gone through, in part because, “being queer, Brown and a bigger guy… society sees [him] an undesirable in the first place”.

On top of that, when sharing his experiences of assault with other queer men, Jaryl assumed they would be empathetic. However, he found that some queer men responded with dismissal and ridicule, presenting a further obstacle to his seeking support.

Thanks to support from friends, Jaryl now has greater clarity about his experience. He said that if he hadn’t had so much stigma holding him back, in fact, he likely would have taken formal action against the perpetrators.

Statistics and awareness in Singapore

Jean agreed with Jaryl that Singapore’s LGBTQ community suffers from a lack of awareness and education when it comes to language and understanding regarding sexual violence. For instance, she has received questions about whether sexual violence even exists in the LGBTQ community, and has even been challenged when she asserts that it does.

While quantitative data on the issue in Singapore is in short supply, Jean cited a survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, which stated that the lifetime prevalence of rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in the US was 43.8% for lesbians and 61.1% for bisexual women, compared with 35% for straight women. Yi Ting added other sources for international statistics, including the Human Rights Campaign and the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network.

For Singapore’s context, Jean cited five key findings on sexual violence and intimate partner violence from Sayoni’s 2018 report on violence and discrimination against LBTQ women in Singapore:

- Punitive and corrective sexual violence was committed on the basis of non-conformity in terms of sexual orientation, gender identity, expression and sex characteristics (SOGIESC).

- Sexual violence was often perpetrated by cisgender and heterosexual men known to survivors.

- LBTQ minors were vulnerable to sexual violence and intimate partner violence.

- Social isolation was often exacerbated by intimate partner violence.

- Heteronormative stereotypes contributed to physical and psychological violence in LBTQ relationships.

Like Jaryl, Jean also pointed out that individuals with intersecting marginalised identities are subject to distinct types of violence. For instance, it is only LBTQ women who are targeted by with “corrective” rape – a highly specific kind of sexual violence – because of their gender and sexual orientation.

Obstacles to reporting

Yi Ting posed the following question to all panelists: What are some issues that LGBTQ people face if they have experienced sexual assault or violence, and wish to report the incident and/or seek help?

Corinna noted that AWARE’s Sexual Assault Care Centre (SACC) does not see a high number of LGBTQ sexual violence cases, which implies that very few LGBTQ people are seeking help in Singapore.

Of the cases Corinna was familiar with, she recalled that a few LGBTQ clients had, prior to coming to SACC, received ignorant remarks from counsellors at other services in Singapore. Many SACC clients had also recounted homophobic behaviour from friends and family members, which again proved a barrier to emotional support.

Of course, any sexual violence case, as Corinna pointed out, comes with obstacles to seeking help, such as victim-survivors’ fears of not being believed, the perpetrator potentially retaliating, and so on. For LGBTQ cases in particular, there are fears surrounding Section 377A: namely, doubts about whether the police would genuinely assist a victim after an assault between two LGBTQ people; as well as concerns that the victim themselves would be prosecuted under 377A. In the event that 377A is repealed, she said, it would still take time for stigma to be removed and for people to trust the police.

Jaryl concurred that 377A stood in the way of his own reporting. He added that reporting can be even harder for certain members of the LGBTQ community than for others—e.g. trans and gender-non-conforming people.

In response to a question about whether LGBTQ people risk being outed in the process of reporting assault, Corinna addressed some concerns that minors in particular might have. Unless a victim-survivor is above 21, there is a risk of the police notifying the victim-survivor’s parents, thus potentially outing the victim-survivor to their family. That said, the gag order policy protects victim-survivors’ identities from appearing in the media, even if case details are disclosed.

Supporting LGBTQ victim-survivors

LGBTQ victim-survivors, Jean said, should be able to access resources such as counsellors, psychiatrists and therapists who are LGBTQ-affirming. Sayoni has created a list of 60 queer-friendly psychotherapists, based on recommendations by LGBTQ persons themselves; this list is available to members of the public upon request.

While Sayoni often vets external references, the organisation does not have the funding to provide professional social services on its own. Instead, a more sustainable strategy is for Sayoni to train and partner with service providers to understand the differences and nuances in sexual violence against LGBTQ people.

Corinna mentioned that while AWARE has collaborated with local universities on how they manage cases of on-campus sexual violence, she remains unsure of whether most local universities currently have the expertise or inclination to prioritise LGBTQ victim-survivors in particular.

Moving past institutional barriers

An attendee asked where Singapore is in terms of overcoming institutional barriers, e.g. in schools, to providing sufficient support for LGBTQ victim-survivors.

Schools are still a long way off from where they should be, said Jean, as evidenced by the recent homophobic incident at Hwa Chong Institution (HCI). She also pointed out that mainstream sexuality education in schools does not cover LGBTQ issues, leaving some children ashamed and isolated, and lacking potentially life-saving information.

Corinna concurred, but added that the HCI incident at least resulted in the homophobic staff member being suspended, which marked the first time in public knowledge that a school official has been suspended for homophobic remarks.

On the other hand, Jaryl said he believes the landscape is changing, albeit slowly. As an educator, he expressed comfort in knowing that LGBTQ teachers are in MOE schools, even if some are not public about their identities. He added that LGBTQ teachers should, if they are able, act as a safe space for their students; it can make a difference for students to have even one individual to turn to.