-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

Press Release: Half of online sexual violence cases seen in 2022 are contact-based

December 11th, 2023 | News, TFSV

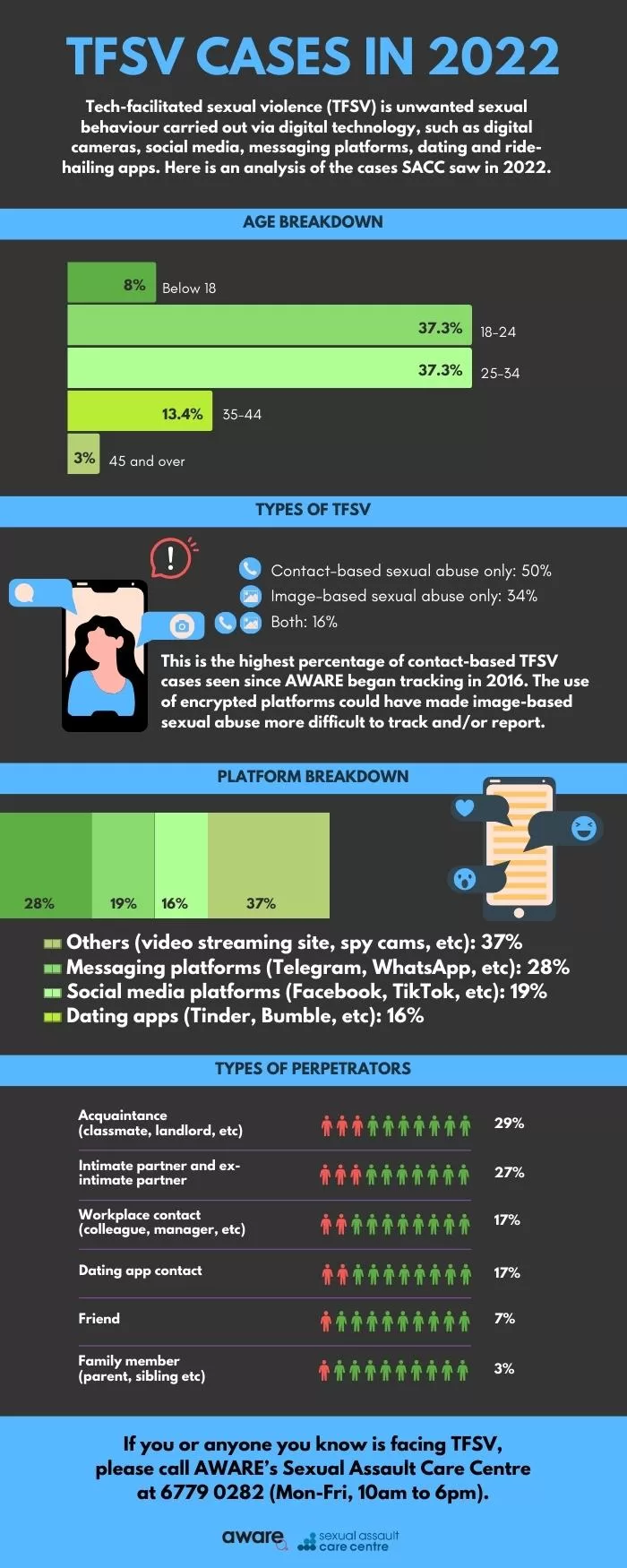

Singapore, December 11, 2023 – Half of the technology-facilitated sexual violence (TFSV) cases seen by AWARE’s Sexual Assault Care Centre (SACC), or 49%, in 2022 involved contact-based sexual violence. Separately, image-based sexual abuse (IBSA) featured in over three in 10 new TFSV cases seen by the SACC, a decline from 49% in 2021.

TFSV is unwanted sexual behaviour carried out via digital technology, such as digital cameras, social media and messaging platforms, and dating and ride-hailing apps. Even though all TFSV cases involve technology, the abuse can occur in person too. Contact-based sexual abuse in TFSV cases refers to cases where one uses technology to make unwanted sexual contact. The initial contact can come from either party.

In total, SACC received 179 TFSV cases in 2022, down from 227 cases in 2021 and 205 in 2020, corresponding with the 20% decrease in the total number of new sexual violence cases seen by the centre.

Nevertheless, the proportion of new cases involving TFSV remained consistent with previous years, at 26%.

“Higher awareness of TFSV has led to more victim-survivors seeking avenues of support,” noted Ms. Sugidha Nithiananthan, Director of Advocacy, Research, and Communications at AWARE.

“Since the effects of TFSV on survivors are similar to those of offline abuse, we welcome the stronger support system that social media platforms, the government, and other organisations are establishing.”

The survivors who sought support from SACC spanned across a wide age range. When SACC had access to the victims’ ages, cases involving those between the ages of 18 and 24 accounted for 37.3% of all reported cases in 2022, while those involving those between the ages of 25 and 34 accounted for another 37.3%; those between 35 and 44 accounted for 13.4%, those under 18 accounted for 8%, and those over 45 accounted for 4%.

Almost eight in 10 perpetrators in the 179 cases were known to victims, with 29% of survivors reporting that their perpetrator was an acquaintance, which included classmates, online friends, and neighbours, among others.

Another 27% reported they experienced TFSV from an intimate or ex-intimate partner, with workplace acquaintances and dating app contacts making the third most common groups of perpetrators at 17% each.

TFSV occurred most commonly on messaging platforms such as Telegram and WhatsApp, with 28% of all cases involving such channels.

The misuse of encrypted platforms has been a consistent trend over the past few years, with various explicit channels being exposed frequently.

Ms. Nithiananthan also warns of the growing complexity of TFSV cases: “With increasingly sophisticated encrypted platforms and generative artificial intelligence, victims may not only find themselves unknowingly featured in explicit content, but face difficulty in securing evidence and reporting such advanced forms of online harms.”

AWARE notes that concrete steps have been taken to combat these malicious acts. The enactment of the Online Safety (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act in Parliament in February 2023 marked a pivotal moment, introducing provisions to hold online communication service providers accountable for non-compliance with the relevant Code of Practice.

Meanwhile, earlier this year, AWARE was the first NGO in Singapore to partner with Bumble on its newly launched anti-abuse tipline.

Despite these milestones, Ms. Nithiananthan remarks that there is still more to be done: “We provided critical recommendations in our 2022 submission to the Public Consultation on Enhancing Online Safety for Users in Singapore, based on our experience supporting victims of TFSV as well as insights from international online safety legislation.”

AWARE also emphasised the importance of introducing additional safeguards for young users, encompassing strict enforcement of minimum age requirements on social media platforms and pornographic websites, mandatory onboarding processes, and the establishment of a dedicated resource centre.

“Our advocacy continues to include the call for the adoption of these recommendations as well as the addition of more safeguards to ensure users are adequately protected in online spaces,” Ms. Nithiananthan concluded.

Annex I: Definitions

Tech-facilitated sexual violence may include sexual harassment, rape, assault, stalking, public humiliation, or intimidation. TFSV behaviours include explicit sexual calls and texts, communications that force people to have sex, and image-based sexual abuse.

Contact-based sexual abuse can include explicit, coercive, and sexually harassing messages or comments on social media, as well as online interactions that don’t involve images and/or videos that lead to sexual violence in real life.

Image-based sexual abuse is an umbrella term for various behaviours involving sexual, nude, or intimate images or videos of another person. AWARE identifies five types:

- The non-consensual creation or obtainment of sexual images: including sexual voyeurism acts such as upskirting, hacking into a victim’s device to retrieve such images, and/or the creation of such images via deepfake technology

- The non-consensual distribution of sexual images: sometimes known colloquially as “revenge porn,” is whereby images shared willingly by a partner or ex-partner are then disseminated to others without the subject’s consent

- The non-consensual viewing of sexual images: whereby a victim is made to view sexual content, such as pornography or dick pics, unwillingly, e.g. over message or email

- Sextortion: whereby sexual images of a victim, obtained with or without consent, are used as leverage to threaten or blackmail that victim in order to solicit further images and/or sexual practices, money, goods or favours

- Others including the capturing of publicly available, non-sexual images which are then non-consensually distributed in a sexualised context, e.g. with sexual comments and/or on a platform known for sexual content, such as the “SG Nasi Lemak” genre of Telegram group

Annex II: Selected Technology-Facilitated Sexual Violence Cases from 2022

Case A: The client discovered that deepfake content featuring her face had been used in explicit material. This content was posted online and widely circulated, causing her much grief.

Case B: The client found her private, intimate photos uploaded to a group chat and a website. When she tried to locate the source, she realised that explicit videos of her were being sold by an unknown entity. Uncertain about the perpetrator’s identity, she hesitated to involve law enforcement as she felt it would be hard to investigate.

Case C: A concerned parent reported that their daughter, who was a minor, had experienced sexual harassment on social media. Peers had set up an account to make explicit remarks about her, which triggered a school investigation after the parent’s notification.

Case D: The client realised he had been ‘catfished’ when he met a dating app contact in person. The perpetrator appeared much older and different from the profile the client had been talking to. During the date, the perpetrator sexually harassed him and forced him to share graphic images of himself. When the client declined future meet-ups, the perpetrator threatened to post the images online.

These cases underscore the urgent need for comprehensive strategies to combat TFSV and provide support for victims. To learn more about AWARE’s efforts or to access resources for combating tech-facilitated sexual violence, please visit aware.org.sg.