-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

AWARE Sees A Sharp Rise in Cases Involving Both Image and Contact-Based Sexual Abuse

November 30th, 2024 | Gender-based Violence, News, Press Release, TFSV

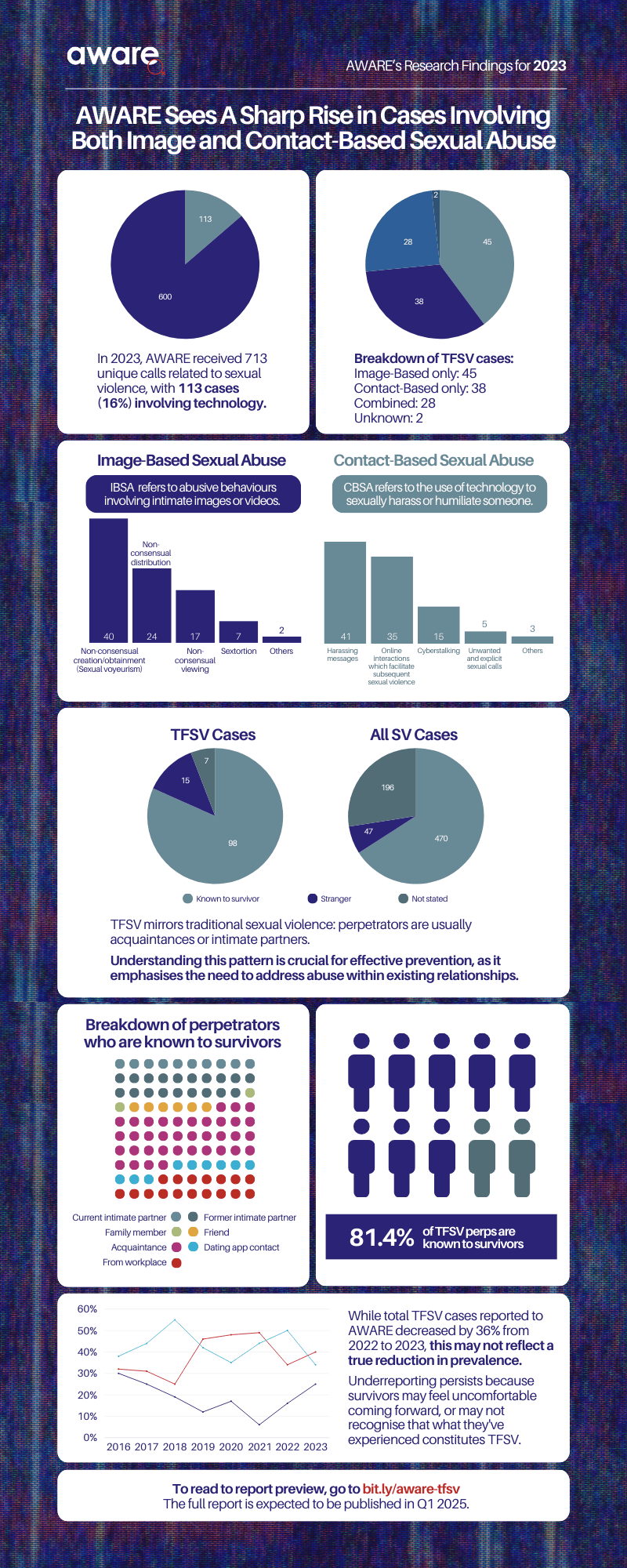

Singapore – AWARE’s Sexual Assault Care Centre (SACC) and Women’s Helpline reported that 25% of all Technology-Facilitated Sexual Violence (TFSV) cases in 2023 involved both Image-Based Sexual Abuse (IBSA) and Contact-Based Sexual Abuse (CBSA) (definitions in Annex I below).

The 19% increase in cases involving both IBSA and CBSA since 2021 reveals how perpetrators are using a combination of image and contact-based methods to harm survivors.

This dual approach intensifies the survivor’s vulnerability, as seen from the cases below.

This overlap highlights the importance of ensuring that legal protections and support systems can respond to both forms of abuse effectively, guaranteeing survivors receive comprehensive help.

According to AWARE, TFSV is defined as sexual violence committed, amplified, or aided through digital technologies or online platforms. In 2023, AWARE received 713 unique calls related to sexual violence, with 113 cases (16%) involving technology.

Image-Based Sexual Abuse (IBSA) and Contact-Based Sexual Abuse (CBSA)

IBSA refers to abusive behaviours involving intimate images or videos. The most prevalent forms reported to AWARE included:

- Non-consensual creation/obtaining of intimate images (40%)

- Non-consensual distribution of intimate images (24%)

- Sextortion (17%)

- Forced viewing of explicit material (2%)

CBSA involves using technology to facilitate unwanted sexual contact, such as:

- Online interactions leading to subsequent sexual violence (41%)

- Sexually harassing messages or comments (35%)

- Cyberstalking (13%)

“AWARE’s data shows that technology increasingly facilitates multifaceted modes of abuse, often through everyday platforms like WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram, and Facebook,” said Sugidha Nithiananthan, AWARE’s Director of Advocacy and Research.

Myths and Realities: Known Perpetrators and Societal Trends

Contrary to the misconception that TFSV perpetrators are anonymous strangers, 81.4% of perpetrators were known to survivors, including:

- Acquaintances (46%)

- Current or former intimate partners (26%)

“These findings debunk the myth of ‘stranger danger.’ Technology amplifies harm from known individuals, making violence more pervasive and harder to escape,” Ms. Nithiananthan said.

Decrease in Reported Cases and the Size of the Problem

While TFSV cases reported to AWARE decreased by 36% from 2022 to 2023, this may not reflect a true reduction in prevalence. Underreporting persists because survivors may feel uncomfortable coming forward or may not recognise that what they’ve experienced constitutes TFSV. Factors could also include survivors seeking support elsewhere.

“We are pleased to see that there are now more services supporting victim-survivors of TFSV, such as the National Anti-Violence and Sexual Harassment Helpline and SHECARES@SCWO, in addition to AWARE’s Sexual Assault Care Centre and Women’s Care Centre helplines,” Ms. Nithiananthan added.

“Despite the addition of two support services, our helplines continue to receive many calls. This, along with ongoing underreporting due to discomfort or lack of awareness among survivors, highlights the magnitude of the problem in Singapore.”

Unique challenges presented by TFSV

TFSV’s digital nature presents unique challenges, such as cross-jurisdictional issues (for example, when the perpetrator is in a different legal region than the survivor) and cases being dismissed due to inadequate evidence.

AWARE reported that 20% of survivors who sought help from authorities felt their cases were not handled satisfactorily, often due to the complexities of digital abuse.

“TFSV survivors can also be revictimised indefinitely because images may resurface anytime, creating a pervasive sense of threat,” Ms. Nithiananthan said.

Recommendations for Addressing TFSV

To better protect survivors, AWARE advocates for legal protection that:

- includes all non-consensual intimate content creation, obtainment, and sharing

- includes messaging platforms like Telegram and WhatsApp

- has a clear process for content takedown with short timelines and easy access for reporting cases.

However, beyond regulatory mechanisms, solutions must also target societal attitudes enabling gender-based violence.

Generative AI, which refers to artificial intelligence that can create new content like images or videos, is being used to create ‘deepfake’ content—realistic but fake media where someone’s likeness is manipulated. For example, in the recent Singapore Sports School incident, students’ images were misused, highlighting the urgent need for intervention.

“This isn’t a prank—it’s abuse,” Ms. Nithiananthan stated. “We need a combination of technology-specific solutions and societal change to combat gender-based violence effectively.”

Annex I: Definitions

Tech-facilitated sexual violence may include sexual harassment, rape, assault, stalking, public humiliation, or intimidation. TFSV behaviours include explicit sexual calls and texts, communications that force people to have sex, and image-based sexual abuse.

Contact-based sexual abuse can include explicit, coercive, and sexually harassing messages or comments on social media, as well as online interactions that don’t involve images and/or videos that lead to sexual violence in real life.

Image-based sexual abuse is an umbrella term for various behaviours involving sexual, nude, or intimate images or videos of another person. AWARE identifies five types:

- The non-consensual creation or obtainment of sexual images: including sexual voyeurism acts such as upskirting, hacking into a victim’s device to retrieve such images, and/or the creation of such images via deepfake technology

- The non-consensual distribution of sexual images: sometimes known colloquially as “revenge porn,” is whereby images shared willingly by a partner or ex-partner are then disseminated to others without the subject’s consent

- The non-consensual viewing of sexual images: whereby a victim is made to view sexual content, such as pornography or dick pics, unwillingly, e.g. over message or email

- Sextortion: whereby sexual images of a victim, obtained with or without consent, are used as leverage to threaten or blackmail that victim in order to solicit further images and/or sexual practices, money, goods or favours

- Others, including the capturing of publicly available, non-sexual images, which are then non-consensually distributed in a sexualised context, e.g. with sexual comments and/or on a platform known for sexual content, such as the “SG Nasi Lemak” genre of Telegram group

Annex II: Selected Technology-Facilitated Sexual Violence Cases from 2023

Case studies

These case studies illustrate the complexity of TFSV cases, where survivors face both direct digital harassment (CBSA) and non-consensual use of intimate images (IBSA):

Case study 1:

Client was being harassed by somebody online after backing out of an online shopping transaction. The harasser downloaded photos of her in swimwear from Facebook and sent her explicit and threatening messages. She blocked him on Facebook and WhatsApp, but he continued to contact her using another phone number.

Case study 2:

Client’s ex-boyfriend used intimate images from when they were in a relationship to blackmail and harass her. When the ex-boyfriend heard that she was going to get married, he obtained her fiance’s contact information and sent him the images. He also threatened to disseminate her images online. The ex-boyfriend was physically abusive during their relationship. After they broke up, he continued to message her with death threats.

Case study 3:

Client was warned by an anonymous account on social media that intimate images of her were circulating online. She was not sure if the claims were authentic and wanted to get to the bottom of the issue. However, the police were unable to investigate because the anonymous account did not provide the client with any evidence. The uncertainty of the situation made her feel extremely uncomfortable and anxious.