-

Advocacy Theme

-

Tags

- Abortion

- Adoption

- Caregiving

- CEDAW

- Disability

- Domestic Violence

- Domestic Workers

- Harassment

- Healthcare

- Housing

- International/Regional Work

- Maintenance

- Media

- Migrant Spouses

- Migrant Workers

- Muslim Law

- National budget

- Parental Leave

- Parenthood

- Polygamy

- Population

- Race and religion

- Sexual Violence

- Sexuality Education

- Single Parents

- Social Support

- Sterilisation

- Women's Charter

What it takes to stop deepfake nudes: Insights from IDEVAW 2024 (1/4)

December 17th, 2024 | Events, Gender-based Violence, News, TFSV

By Athiyah Azeem. Adilah Rafey and Racher Du contributed to this article.

Explicit nonconsensual deepfakes are making headlines right now.

Recently, news reported that male Singapore Sports School students created and circulated deepfake nudes of female students and teachers. Less than two weeks later, anonymous actors attempted to extort a Ministry of Health agency with explicit deepfakes of their staff, and extort 100 public servants, including five ministers, using “compromising” videos. News media reported all three incidents in November alone.

- There is a rise in nonconsensual deepfake nudes and other types of tech-facilitated sexual violence

- The people who use intimate images or create deepfake images to commit sexual violence are often the people you know

- Developers are racing to implement guardrails in their AI to prevent it from creating deepfake nudes, but bad actors keep breaking these guardrails

- The Ministry of Digital Development and Information is creating an agency that could quickly order takedowns of posts with TFSV without needing to make a police report. This could give survivors relief and agency

- Comprehensive sex education and consent education can prevent future generations from committing TFSV

This isn’t new. Nonconsensual deepfake nudes are a type of Technology-Facilitated Sexual Violence, or TFSV, where perpetrators commit sexual violence online.

Every year, AWARE receives a sizable number of callers to our Sexual Assault Care Centre (SACC) helpline about TFSV. Out of 713 calls about sexual violence to SACC in 2023, 113 calls, or 16%, involved TFSV.

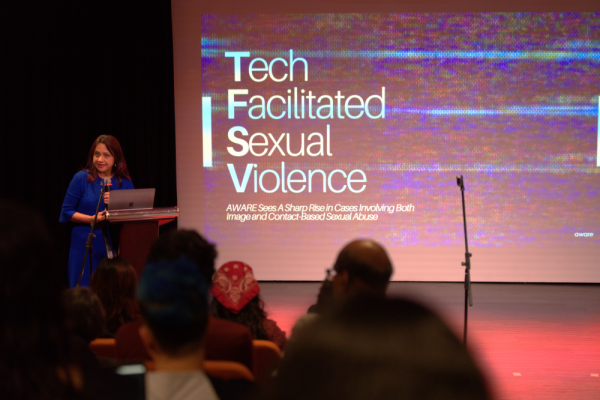

Sugidha Nithiananthan, AWARE’s Director of Advocacy and Research, presented what we’ve learnt from these calls at IDEVAW 2024—a full-day event on 30 November 2024 by AWARE where advocates and experts convened to talk about gender-based violence.

“A client’s ex-boyfriend used intimate images from when they were in a relationship to blackmail and harass her,” Sugidha said to the audience. “After they broke up, he continued to message her with death threats.”

This is an incident where the perpetrator committed both IBSA and CBSA. IBSA is Image-Based Sexual Abuse. Non-consensual deepfake nudes are a type of IBSA. CBSA is Contact-Based Sexual Abuse. CBSA includes online interactions that lead to sexual violence, sexually harassing messages or comments and cyberstalking.

In 2023, 25% of perpetrators committed both IBSA and CBSA—an increase from 16% in 2022 and 6% in 2021.

It is vital to understand that the people who commit TFSV are not strangers—81.4% of TFSV perpetrators are known to the survivors. They’re mostly acquaintances, or intimate partners and ex-partners.

“TFSV is not a niche form of violence that only affects a subset of people who choose to date online or live their lives on online and social media,” Sugidha said. “Digital technology is amazing but also adversely affecting women in gendered and sexualised ways.”

To understand the digital technology, chiefly AI, that is used to perpetuate IBSA, Mohan Kankanhalli, Director of NUS’ AI Institute, introduced us to how developers can tackle it.

“Anybody with the ability to click a mouse can actually create deepfakes. Which is scary,” Mohan said.

But developers can implement guardrails on their AI to prevent it from creating nudes. For one, they can make the AI refuse to create images when they receive a prompt that has keywords like ‘nude’ or ‘naked.’

Even then, perpetrators can input the keywords in unique ways, like ‘nude%’ or ‘&*nude’, and the AI would still recognise the word “nude” and generate an explicit image. So, Mohan said it is difficult to build keyword-based guardrails.

Watermarking technology could impose an unremovable brand on images to help survivors and authorities track which AI engine created it. But Mohan said this technology just isn’t there yet.

Right now, developers are working on machine unlearning, where they get the AI engine to forget how to generate a naked body in the first place.

After their presentations, Sugidha and Mohan joined Stefanie Thio, Chairperson of SG Her Empowerment, to talk about how to stop incidences of TFSV.

SG Her Empowerment operates SHECARES@SCWO, a support centre for survivors of online harms. Stefanie said she was excited by a recent announcement by the Ministry of Digital Development and Information, who said they would create an agency to quickly take down online harms like intimate image abuse.

According to MDDI, this agency will allow victim-survivors to report abusive posts without needing to make a police report. This is important, as the criminal consequence of TFSV can stop survivors from making a report—especially when they know the perpetrator.

“What is important about this is not just how quick the takedown is, I think it is the sense of agency you give somebody who has been victimised,” Stefanie said. “It will signal to the community that these are bad actions.”

That said, Stefanie said that it is important for perpetrators to understand that what they are doing is wrong.

She introduced the idea of making a code of practice that schools can introduce to their students. This way, students understand and internalise that they should not commit or enable TFSV.

Sugidha and Stefanie talked about working together to create that code of practice.

On the developer side, Mohan said that having more women in tech will make TFSV more salient to tech companies and “get their due importance.” He said when tech companies prioritise creating better guardrails on their AI, it can help curb TFSV.

According to Sugidha, Stefanie and Mohan’s conversations, the technological solutions to TFSV are limited. As long as the technology exists on the internet, people will continue to use deepfake nude technology to commit IBSA to women they know.

And while it is true that putting images of yourself on social media increases your vulnerability to IBSA, TFSV does not just affect people with an online presence, Sugidha said. It is just a new way of perpetuating gender-based violence.

The reason why someone would commit TFSV, is often because they don’t respect the consent and autonomy of women and their bodies. Sugidha said it is important to teach people comprehensive sex education, including consent, gender stereotypes, gender-based violence and gender inequality, so future generations are less likely to commit TFSV.

You can read more about our TFSV findings in our press release.